Overview

In 'Here Be Dragons!' Kalki Dāsa explores the mythical fire-breathing monsters of yore, and discovers that although these creatures are present within many different ancient cultures, the dragon prototype seems to be found in the Vedic literature.

Dragons have captured our imaginations since before we can remember. For some, dragons represent raw untamed nature, strength, and hidden knowledge in many cultures. For others, dragons represent evil, and strike fear into the hearts of men. Throughout history, people have written about these mythical creatures based on the legends they inherited from their ancestors, and vary from one tradition to the next. One thing is for sure, dragons are awe-inspiring creatures and everyone can attest to that.

From the northern lands of Europe, down to the South Asian seas, dragons are a repeating theme in ancient cultures and give us a clue to how our ancestors lived, and thought about the world around them.

The Bible tells the following story about the God Yahweh and his battle with the Leviathan monster,

“On that day the Lord shall punish

with his sharp, great, and strong sword,

Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent;

He will slay the dragon that is in the sea.” (Old Testament, Psalm 74:13–14)

Earlier on in Mesopotamia, the story of Bel Marduk versus the goddess Tiamat is told in the Akkadian ‘Enuma Elish’,

“Marduk raised the thunderbolt, his mighty weapon, he mounted his chariot, the storm unequaled for terror, he harnessed and yoked unto it four horses, destructive, ferocious, overwhelming, and swift of pace; As the dragon Tiamat opened her mouth to its fullest extent, he (Marduk) drove in the evil wind, while she had not shut her lips. The terrible wind filled her body, and her courage was taken from her, and her mouth she opened wide. He seized the spear and burst her belly, he severed her inward parts. He pierced her heart. He overcame her and cut off her life;” (The Akkadian Enuma Elish, Tablet 4)

In Greek mythology, Zeus (God of thunder) also killed a fire breathing monster named Typhon,

“Zeus thundered hard and mightily: and the earth around resounded terribly and the wide heaven above, and the sea and ocean’s streams and the nether parts of the earth. Great Olympus reeled beneath the divine feet of the king as he arose and earth groaned thereat. And through the two of them heat took hold on the dark-blue sea, through the thunder and lightning, and through the fire from the monster, and the scorching winds and blazing thunderbolt.” (‘Theogony’ by the Greek poet Hesiod)

Another appearance of this legend comes from Norse mythology, between Thor (God of thunder) and Jörmungandr, the world serpent. The following story narrates how once Thor went fishing, and hooked the great serpent on his line. After getting a whack on the head, Jörmungandr sank back down into the ocean,

“Drew up boldly

The mighty Thor

The snake with venom glistening,

Up to the side;

With his hammer struck,

On his foul head’s summit,

Like a rock towering,

The wolf’s own brother.

The icebergs resounded,

The caverns howled,

The old earth

Shrank together:

At length the fish

Back into the ocean sank.”

(Hymiskvida: The Lay of Hymir verses 23-24)

The Norse legends also tell that at the end of the cosmic cycle known as Ragnarök, Jörmungandr will engulf the universe with the flames coming from his mouth, and will face Thor in a mighty duel.

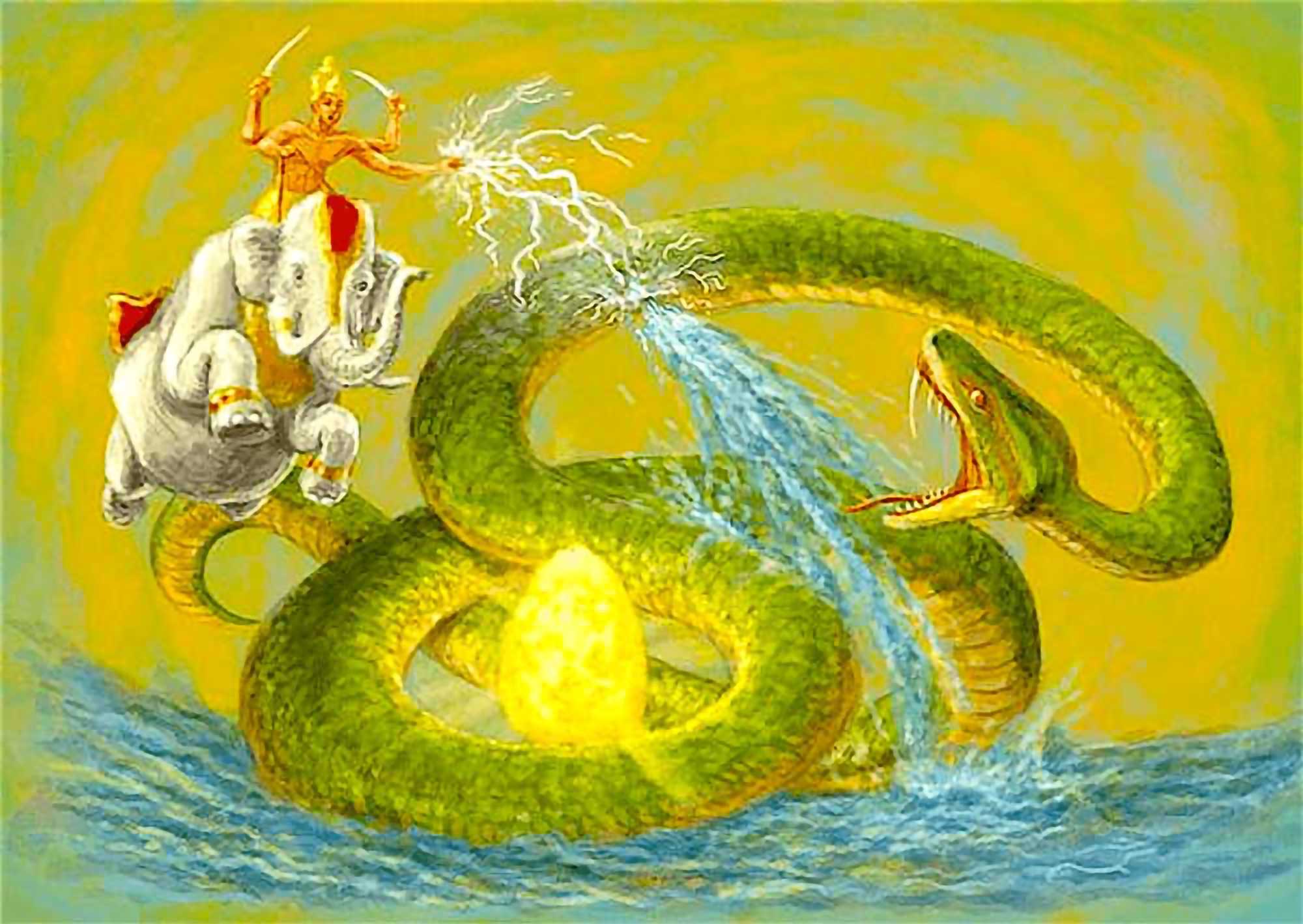

(From top left clockwise: Tiamat and Marduk, Thor and Jörmungandr, Yahweh and Leviathan, Zeus and Typhon)

(From top left clockwise: Tiamat and Marduk, Thor and Jörmungandr, Yahweh and Leviathan, Zeus and Typhon)

The earliest source of this battle is found in the Ṛg Veda of Ancient India in the epic fight between Lord Indra, and the demon Vṛtra,

“I will declare the manly deeds of Indra, the first that he achieved, the Thunderbolt-wielder.

He slew the dragon (Ahi), then disclosed the waters, and cleft the channels of the mountain torrents.

He slew the dragon lying on the mountain: his heavenly bolt of thunder Tvaṣṭā fashioned.

Like lowing kine in rapid flow descending the waters glided downward to the ocean.

Impetuous as a bull, he chose the soma and in three sacred beakers drank the juices.

Maghavān (Indra) grasped the thunder for his weapon, and smote to death this firstborn of the dragons.

When, Indra, thou hadst slain the dragon’s firstborn, and overcome the charms of the enchanters,

Then, giving life to Sun and Dawn and Heaven, thou foundest not one foe to stand against thee.

Indra with his own great and deadly thunder smote into pieces Vṛtra, worst of demons.

As trunks of trees, what time the axe hath felled them, low on the earth so lies the prostrate dragon.” (Ṛg Veda, Hymn 32)

(Indra battling Vṛtrāsura)

Some researchers have suggested that this story of Indra slaying Vṛtrāsura and releasing the waters of the mountains could be a historical reference to the end of the last Ice Age, at a time that the climate was rapidly changing, causing massive glaciers to break up. Whichever the case, it’s interesting to see how the Akkadian, Greek, and Norse cultures inherited this story from the Ṛg Veda, the oldest scripture in the Vedic canon.

It seems that dragons first made their appearance in Europe during Greco-Roman times. From 300 BC to 250 BC, the famed general Alexander of Macedonia conquered as far as the river Ganges in India, bringing back with him to Greece many treasures from his exploits. In his book, ‘De Natura Animalus’, the Roman writer Claudius Aelianus gives an interesting account of Alexander’s during his time in India,

“When Alexander threw some parts of India into a commotion, and took possession of others, he encountered among many other animals a serpent which lived in a cavern and was regarded as sacred by the Indians who paid it great and superstitious reverence. Accordingly, Indians went to all lengths imploring Alexander to permit nobody to attack the serpent; and he assented to their wish. Now as the army passed by the cavern and caused a noise, the serpent was aware of it. (It has, you know, the sharpest hearing and the keenest sight of all the animals.) And it hissed and snorted so violently that all were terrified and confounded. It was reported to measure 70 cubits (105 ft) although it was not visible in all its length for it only put its head out. At any rate its eyes are said to have been the size of a large, round Macedonian shield.” (Claudius Aelianus, ‘De Natura Animalus’ 200 AD)

Nearly two thousand years ago, the Greek sophist Apollonius of Tyana also went to India following in the footsteps of his hero Pythagoras, (who went 300 years prior to Alexander). In a biography of Apollonius of Tyana, an account of his experience with ‘drakons’ is given,

“They (the Indians) embroider golden runes on a scarlet cloak, which they lay in front of the animal’s burrow after charming them to sleep with the runes; for this is the only way to overcome the eyes of the drakon, which are otherwise inflexible, and much mysterious lore is sung by them to overcome him. These runes induce the drakon to stretch his neck out of his burrow and fall asleep over them: then the lndians fall upon him as he lies there, and despatch him with blows of their axes, and having cut off the head they despoil it of its gems.” (Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 3. 6 -9)

Whether or not these men truly witnessed the creatures, several interesting points can be made. Firstly, Alexander’s account like many of the Vedic accounts speaks of a ‘serpent’ rather than a dragon. It’s important to note that although most translations of ancient texts use the word ‘dragon’ due to being translated into modern languages, this may not exactly be the ‘dragons’ that we have in mind. In fact, when the Vedic literatures speak of ‘dragons’, it’s being translated from ‘ahi’ which means serpent. The Greek word ‘drakon’ also translates as serpent.

Additionally, Apollonius of Tyana’s account mentions how runes were sung by drakon hunters in order to overcome them. This is probably referring to mantras chanted to charm snakes, as can be seen even today in India with those who practice nāga-pūjā, or serpent worship.

In regards to the gems which the hunters obtained from the Indian ‘drakons’, a practice still exists today in India where gemstones called nāgamani are removed from the heads of king cobras and kept as auspicious tokens.

The Purāṇas also speak of a race of divine beings called Nāgas who live in a subterranean abode, where everything is lit by glowing gems on their heads,

“Since there is no sunshine in those subterranean planets, time is not divided into days and nights, and consequently fear produced by time does not exist. Many great serpents (Nāgas) reside there with gems on their hoods, and the effulgence of these gems dissipates the darkness in all directions.” (Bhāgavata Purāṇa 5.24.11-12)

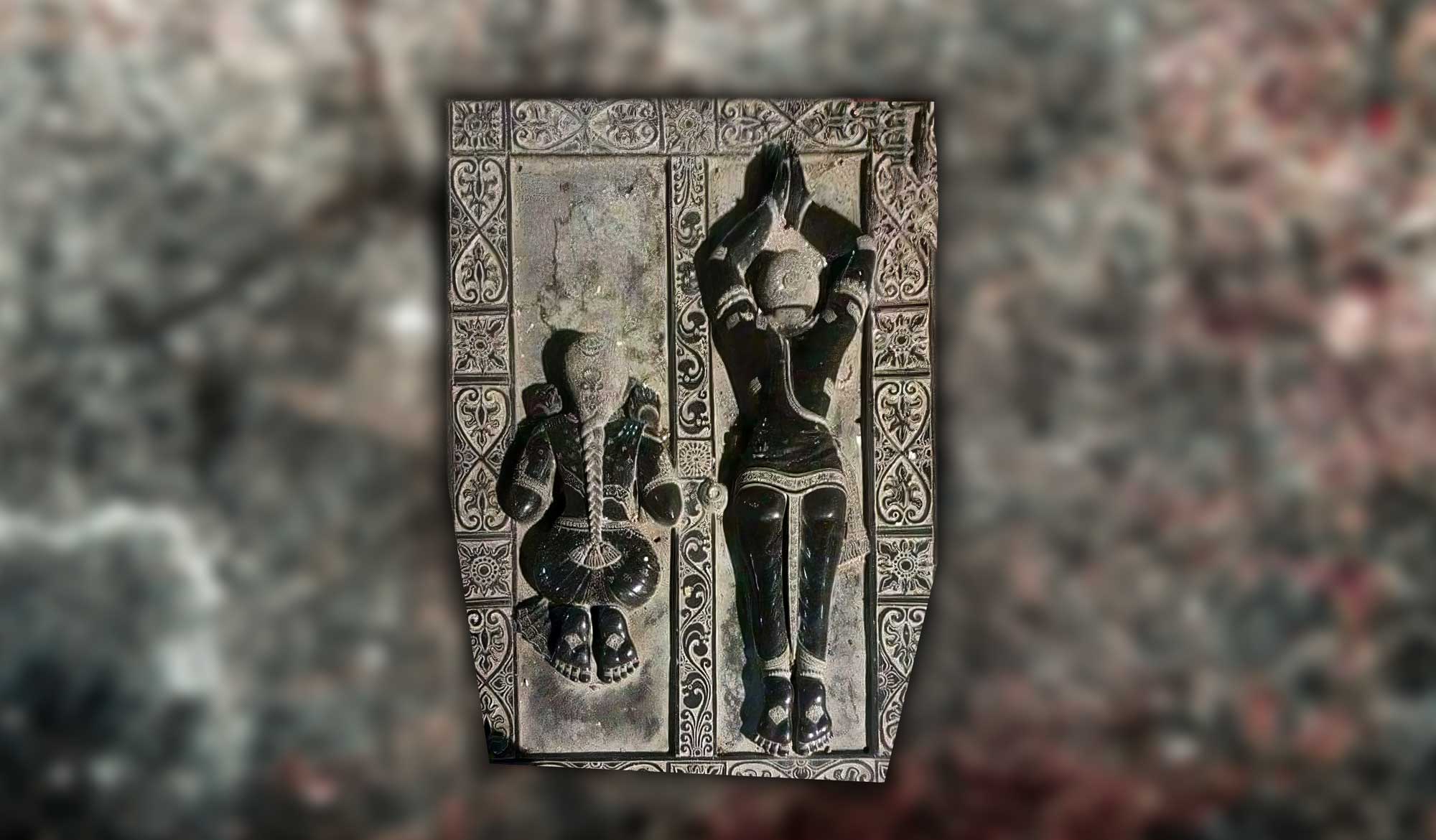

(Carvings from the Konark sun temple in Orissa and Badami cave temple in Karnataka depicting the Naga race of ancient India)

Another reference to a powerful serpent race living in subterranean realms is mentioned elsewhere in Native North American folklore, as well as a divine bird that rules over the heavens,

“In Algonquian mythology, the Thunderbird controls the upper world while the underworld is controlled by the underwater panther or Great Horned Serpent. The Thunderbird creates not just thunder (with its wing-flapping), but lightning bolts, which it casts at the underworld creatures.” (Haltiner, Robert E. (1984). NAUB-COW-ZO-WIN Discs from Northern Michigan)

“The Menominee of Northern Wisconsin tell of a great mountain that floats in the western sky on which dwell the thunderbirds. They control the rain and hail, and delight in fighting and deeds of greatness. They are the enemies of the great horned snakes (the Misikinubik) and have prevented these from overrunning the earth and devouring humankind. They are messengers of the Great Sun himself.” (George Lankford. ‘Native American Legends of the Southeast: Tales of the Natchez, Caddo, Biloxi, Chickasaw, and other Nations’.”

A matching description of the Thunderbird is given in the Mahābhārata:

“Indra, observing Garuḍa flying with great speed, hurled his thunderbolt towards the bird. Garuḍa, despite being struck with the weapon, smiled and told Indra in polite words, “O King of the Devas, I respect the Sage Dadhīci from whose backbone this vajra (thunderbolt) weapon was made; I respect you too. To honour this, I will shed a single feather. But know that I have not felt any pain due to this weapon”.

The Purāṇas also refer to Garuḍa as ‘uraṅga-vidviṣā’ or ‘Enemy of snakes’,

“Mahātala is the abode of many-hooded snakes (Nāgas), descendants of Kadrū, who are always very angry. The great snakes who are prominent are Kuhaka, Takṣaka, Kaliyā and Suṣeṇa. The snakes in Mahātala are always disturbed by fear of Garuḍa, the carrier of Lord Viṣṇu, but although they are full of anxiety, some of the them nevertheless sport with their wives, children, friends and relatives. (Bhāgavata Purāṇa 5.24.29)

A more descriptive account of the Nāga underworld is given in Mahābhārata, wherein the Nāga king Takṣaka stole the golden earrings of a brāhmaṇa (Uttaṅka) and entered into Mahātala. Lord Indra and his thunderbolt are again mentioned in this connection,

“The disguised Takṣaka, suddenly quitting the form of the beggar, assumed his own real form, and quickly disappeared into a large hole in the ground. Entering the region of the Nāgas, he proceeded to his own abode. Uttaṅka remembering the words of the queen, pursued Takṣaka. He began to dig open the hole with a stick, but did not make much progress. Seeing his distress Lord Indra sent his thunderbolt to his assistance. Saying, “Go and help that brāhmaṇa.” The thunderbolt entering into the stick enlarged the hole. Uttaṅka entered into the hole after the thunderbolt and thus entering it he saw the land of the Nāgas with hundreds of palaces, elegant mansions, with turrets and domes, and gateways, with wonderful arenas for various games and entertainments.” (Mahābhārata Ādi-parva 3.127-134)

Interestingly enough, Takṣaka is described as a ‘flying serpent’ in the Mahābharata. After killing the world emperor Mahārāja Parikṣit, Takṣaka even lets out a roar just as we might expect to hear coming from a dragon,

“The ministers who beheld the king (Mahārāja Parikṣit) in the coils of Takṣaka became pale with fear and wept in exceeding grief. And hearing the roar of Takṣaka, the ministers all fled. And as they were running away in great grief, they saw Takṣaka, the Nāga king, that wonderful serpent, coursing through the blue sky like a streak with the colour of the lotus. His coursing through the sky looked like the vermillion line in the middle of the dark masses of a lady’s hair.” (Mahābhārata Ādi-parva 44.1-3)

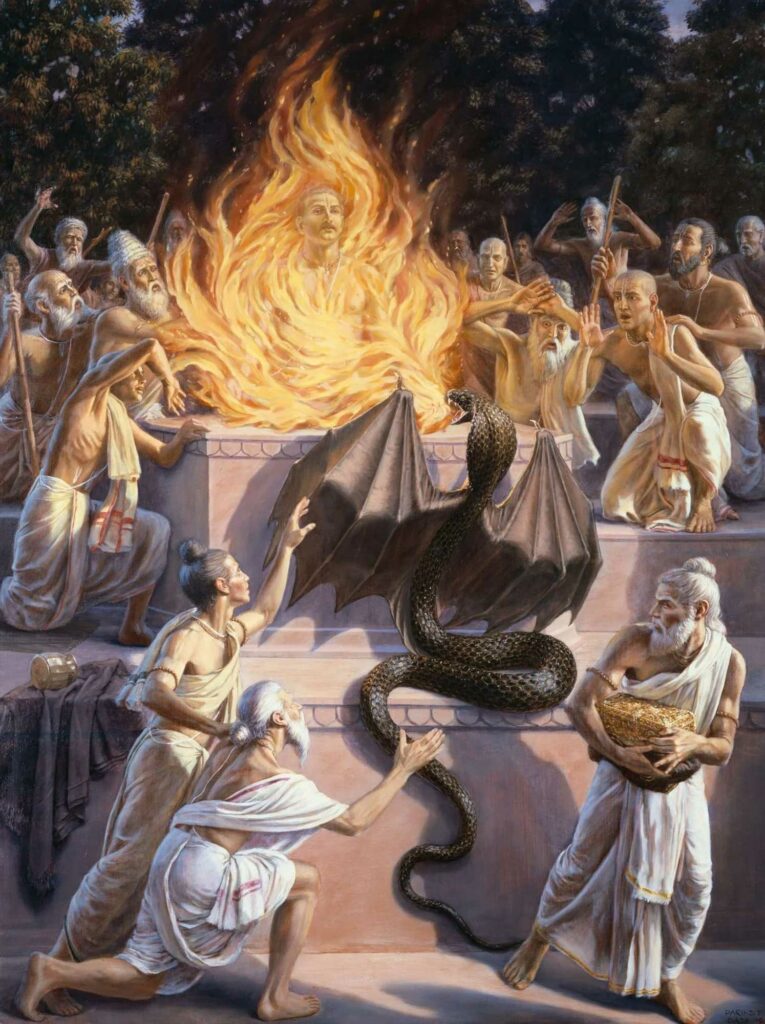

(Takṣaka burns Mahārāja Parikṣit to ashes)

(Takṣaka burns Mahārāja Parikṣit to ashes)

The Purāṇas also describe that when Takṣaka bit the king, his poison created flames which burned the King’s body to ashes. In order to stop the Sage Kaśyapa, who knew the science of counteracting the venom, he bribed him with a valuable treasure,

“O learned brāhmaṇas, the snake-bird Takṣaka, who had been sent by the angry son of a brāhmaṇa, was going toward the King to kill him when he saw Kaśyapa Muni on the path. Takṣaka flattered Kaśyapa by presenting him with valuable offerings and thereby stopped the sage, who was expert in counteracting poison, from protecting Maharaja Parikṣit. Then the snakebird, who could assume any form he wished, disguised himself as a brāhmaṇa, approached the King and bit him. While living beings all over the universe looked on, the body of the great self-realised saint among kings was immediately burned to ashes by the fire of the snake’s poison.” (Bhāgavata Purāṇa 12.6.11-13)

The iconography of flying serpents is common to a number of ancient cultures. In México, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl (Aztec) or Kulkulkan (Mayan, Olmec) was worshipped as the God of Gods. The Chinese word ‘feilong’ (fei = flying, long = serpent) translates as a flying type of serpent described with multicoloured feathers and the tail of a phoenix. In Ancient Egypt, the fertility Goddess Wadjet was also depicted as a winged serpent.

In China, Takṣaka is mentioned as one of the eight dragon kings of the world. Dragons are seen as divine beings in Chinese culture and have been worshipped as far back as seven-thousand years ago. Traditionally, the Chinese depicted their dragons as decorated serpents with four legs. The first emperor of the Han dynasty, Lui Bang is believed to be descended from a dragon, after his mother dreamed that a dragon came down from the clouds into her room and impregnated her. Lui Bang overthrew the Qin dynasty and founded the Han dynasty in 206 BCE. The forefathers of Ancient Cambodia and Vietnam are also believed to be descended from a nāga princess.

How so many parallels can be drawn between the Vedic tradition and various world cultures seem to indicate how Vedic culture must have spread in the distant past. Historians are now beginning to understand how rulers from the ancient South Asian maritime empire known as the Cham, or Khmer conquered far and wide, and probably landed in the Americas far earlier than Spanish explorers, and even the Vikings. Since the Cham rulers were originally part of the Vedic culture, they likely brought many of their legends and deities along with them.

With all this in mind we can understand where the idea of flying serpents, and serpent worship likely originated, but when did these creatures morph into the classic dragons with bat-wings, and spiky tails we know of today?

(Chinese dragon, Wadjet the winged serpent, Beowulf fights the dragon and Quetzcoatl the aztec feathered serpent)

The appearance of these kind of dragons seem to come about during the Middle Ages, in Old English and Germanic Folklore. In the Old English epic ‘Beowulf’, we see perhaps the first instance of modern dragons like we see in T.V. shows like ‘Game of Thrones’, or J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘The Hobbit’. It is from folklore like ‘Beowulf’, and the Germanic ‘Volsung Saga’ where many fantasy authors got their inspiration for the dragons in their novels. A brief narration is given as follows after a beggar stole a goblet from the Dragon’s treasure hoard in ‘Beowulf’,

“When the dragon awoke, trouble flared again.

He rippled down the rock, writhing with anger

When he saw the footprints of the prowler who had stolen

Too close to his dreaming head.

So may a man not marked by fate

Easily escape exile and woe

By the grace of God.

The hoard-guardian

Scorched the ground as he scoured and hunted

For the trespasser who had troubled his sleep.

With fierce impatience; his pent-up fury

At the loss of the vessel made him long to hit back

And lash out in flames. Then, to his delight,

The day waned and he could wait no longer

Behind the wall, but hurtled forth

In a fiery blaze. The first to suffer

Were the people on the land, but before long

It was their treasure-giver who would come to grief.” (‘Beowulf’, lines 2300-2310)

During the Middle Ages, the Church associated serpents and dragons with evil. Stories dating as far back to the 9th century, like the tale of Saint George served as testament to show how evil dragons could be. The Dragon mentioned in the tale of St. George supposedly attacked villages and farmers. People even had to regularly sacrifice their sheep to the dragon, just to keep it pacified.

(Saint George and the dragon)

(Saint George and the dragon)

The legend of Saint George and the dragon actually comes from a Roman general named Theodore Tiron, who was famous for defeating a ‘draco standard’ (military arrangement). Theodore Tiron and George of Lydda were both Christian soldiers, and protested the worship of ‘pagan’ gods during the 5th Century A.D. In order to the preserve the deities and legends that the common people were attached, Church legislators merged these ancient legends like ‘Thor vs. Jörmungandr’ and ‘Zeus and Typhon’ into the lore of ‘Saint George and the Dragon’. Monuments like the ‘Gosforth Cross’ in England, dated to the 10th century A.D. illustrate how numerous earlier pagan legends, became absorbed by Imperial Christianity during the Middle Ages.

Another probable source for what influenced Medieval dragons is that excavations made during the Middle Ages uncovered the bones of dinosaurs and other large reptilian beasts from bygone ages. To early palaeontologists under the sway of the church, these fossilised remains were probably identified as Biblical monsters like the ‘Leviathan’, or St. George’s dragon rather than fossils of the prehistoric creatures we know about today.

Unsurprisingly, dragons came to be identified with the most terrifying qualities from the cultures they originated from — developing beet-red eyes, bat wings, fearsome talons, and a temper like you wouldn’t believe. Qualities of mythical creatures like the Basilisk, the Drakon, the Wyvern, and the Gryphon all merged together to form the fantastic composite animal we know today as the dragon. Moreover, elements such as fire breathing, obsession with treasure, and their dwelling in the depths of oceans, or dark cavernous abodes strongly indicates that Vedic legends like Indra vs. Vṛtrāsura and the flying serpent Takṣaka are the prototype for all other dragon legends throughout the world.

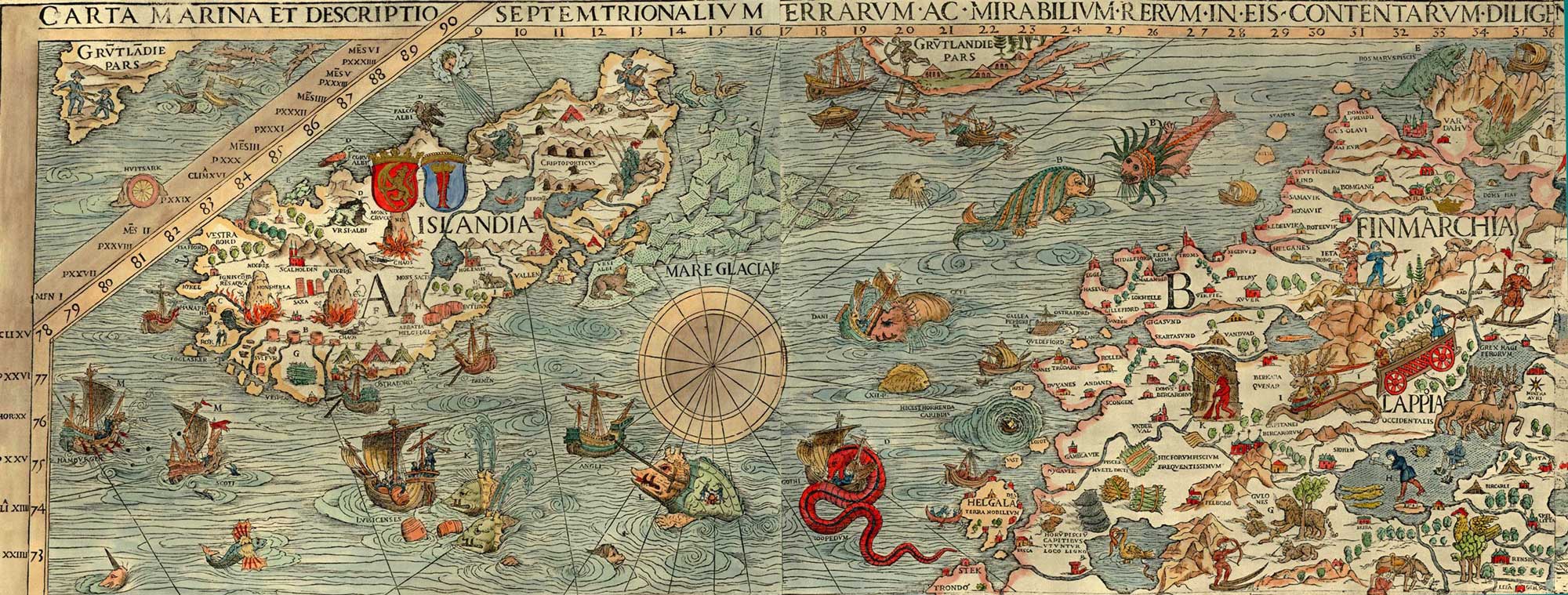

Dragons have always had an attractive quality which has led many people throughout history to fear them, or adore them. This quality of dragons as dangerous, shadowy creatures has come to symbolise power and the unknown, mystical realm. It is likely for this reason that Medieval map makers marked uncharted territories with the inscription, ‘Here be dragons’ to indicate either a hidden treasure or certain death. In either case, if we dare to explore the unknown, we can surely expect an adventure lies ahead…

Related Articles & Books

- 📖 When Wise Men Speak Wise Men Listen by Swami B.G. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja (Book)

- Vedic Global Civilisation by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- UFOs – Is Anyone Out There? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Modern Science and the Vedas by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Giants – Myth or Fact? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Timiṅgila – Myth or Fact? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Makara – Myth or fact? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Lost Ancient Technology by Kalki Dāsa

- Here Be Dragons! by Kalki Dāsa

- The Great Flood – Are Manu and Noah the Same Person? by Kalki Dāsa

- Zarathustra and The De-evolution of Theism by Kalki Dāsa

- Did Darwin Borrow His Theory of Evolution from the Vedas? by Kalki Dāsa

Further Reading

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.

Ātma Samīkṣā – The Value of Introspection

In this article, "Ātma Samīkṣā – The Value of Introspection" Kalki Dāsa highlights the importance of introspection in the life of a devotee and especially in relation to the worldly environment that surrounds us. He also explains how transcendental sound influences our capacity to introspect.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.

Ātma Samīkṣā – The Value of Introspection

In this article, "Ātma Samīkṣā – The Value of Introspection" Kalki Dāsa highlights the importance of introspection in the life of a devotee and especially in relation to the worldly environment that surrounds us. He also explains how transcendental sound influences our capacity to introspect.