Overview

In 'Hard as a Thunderbolt, Soft as a Flower' which was first published in 'Gauḍīya Touchstone' Issue 1, Swami B.G. Narasiṅgha interviews Kiśora Dāsa and Kālakāṇṭhi Dāsī, followers of Swami Sadānanda, the first foreign disciple of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura.

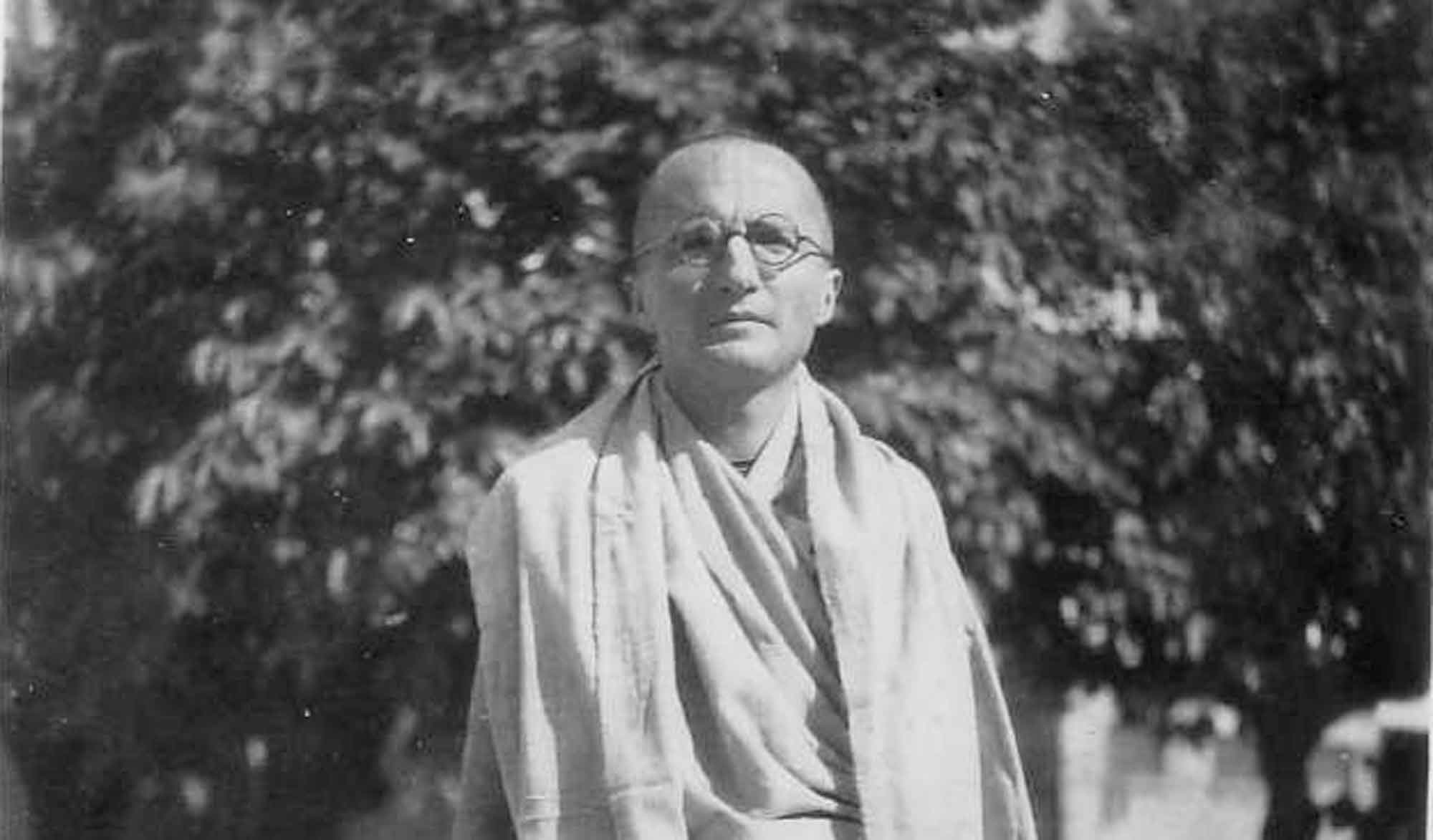

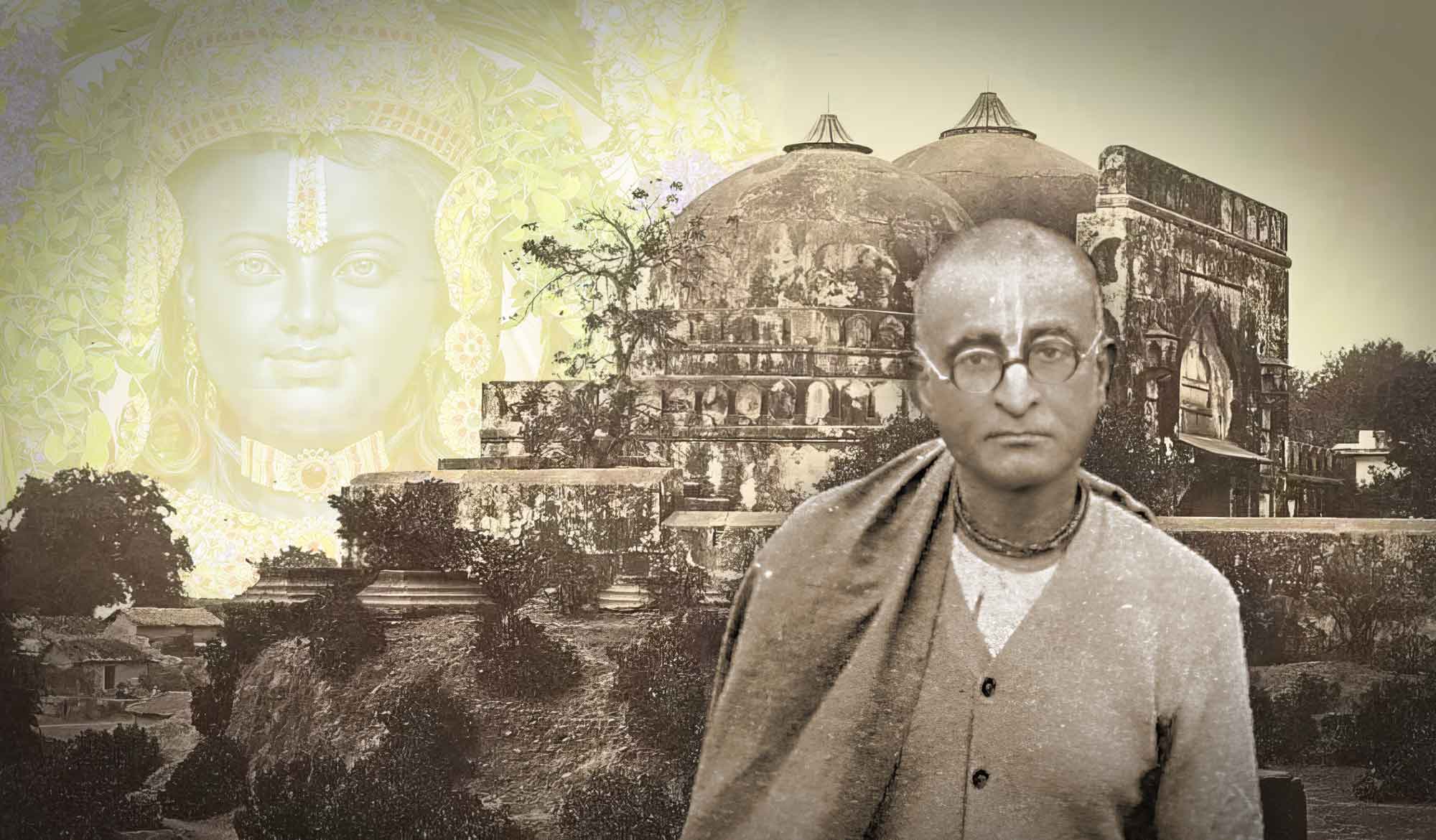

(Swami Sadānanda, as he is popularly known, was the first western adherent to Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava philosophy in the 20th century. Sadānanda was of German descent. He traveled to India, became an initiated disciple of Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī and was later interned in a prisoner of war camp in India during World War II. Upon his release at the end of the war, Sadānanda traveled extensively in India and eventually returned to Europe where he established a modest following in Sweden, Switzerland and Germany. That following of disciples continues to this day.)

Q) How did Swami Sadānanda come in contact with the teachings of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism?

In the winter of 1933, when he was 25 years old, he met Swami Vana in Berlin and through him he later got the work Sree Kṛṣṇa Caitanya by Prof. Sanyal. There he found the answers to all the questions he had nurtured for many years:

“It is since the year 1922 that my life was engaged in the search for a deeper conception of Religion, Truth and Godhead – than the religion of my confession. I have never been interested in worldly learnings. I have been studying the Comparative History of Religion and reading the best books and scriptures of the different religions – not for scholarly purpose but for finding out the way of the realisation of the natural function of the soul.” (Letter to Swami Vana, January 12, 1934)

This led him to intensive studies of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism and further contact with Swami Vana and Bhakti Pradip Tirtha Maharaja, who both gave him initiation at the matha in London in the beginning of 1934. In April Sadānanda wrote in his first letter to Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī:

“Blessed by Your Divine Grace I was initiated by Sree Swami Vana and received the holy Name from Sree Tirtha Maharaj.”

Sadānanda then worked for the mission both in England and Germany until Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī invited him to join his mission in India, where Sadānanda arrived in September 1935, together with Swami Vana and Baron Von Koeth from Germany.

Q) Did Swami Sadānanda ever speak about his years in the Gauḍīya Maṭha in India? What places, what events, and what personalities and Godbrothers did he mention?

He could only serve his gurudeva in the Gauḍīya Maṭha from September 1935 till January 1937. From his notes it seems that he followed Bhaktisiddhānta on his tours, took notes from his lectures etc. Most of the time he was certainly engaged in studying the śāstrams, preparing lectures himself and writing articles for The Harmonist. Not much is known about his relation to his Godbrothers during this time but we know that he never felt at home in the Gauḍīya Maṭha.

Moreover already then his health was fragile. He never believed in “organized religion”, and in his article in The Harmonist, “Society – Community – Math”, one can see that his vision of the true matha was rather utopian, as it implies a society of absolutely pure Vaiṣṇavas. He seems to have had difficulties in fitting himself into the real organisation, with all its shortcomings. In some notes from Darjeeling, July 12, 1936 one can read:

“You must have your own sensitive, i.e. organic system, tailor-made, no suit off the peg. It is only when you subserve yourself and your environment to the necessities and rules of living according to your personal conditions that you can render your fellow beings a service. Judges of character can see through your automatic skeleton suit in the same manner as you can see through the armour of conventions, into the corrupt “substance” of the kernel – insincerity. Only those who are truly existing (who are “sat”/prema-bhaktas) can teach – and those are the last who adopt the pose of a teacher. The others can “talk about” being more humble than a blade of grass, but cannot live a comrade-leaderfellowship as Christ has done, because in this case they fear – with perfect justice – that they would lose the possibility to be a teacher, in other words: their “respect”. In the best possible way, you should withdraw from the marketplace and shape your life, in all expressions of your being, as a direct consequence of your true relation to God. Watch out for stereotypes, which will kill you, and what is worse, the thing itself. Be free!”

Q) Did Swami Sadānanda often speak about his guru, Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura? What sort of things did he say?

Everything Sadānanda did was in the spirit of ‘Prabhupāda’s sevā’ and when Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura disappeared Sadānanda suffered immensely. Being extremely ill in India, sometimes unable to perform his shastra-seva, he often writes to Vāmandāsa in Sweden: “When will Prabhupāda finally call me back?” and in the next moment he thinks of Vāmandāsa and his friends in Sweden and writes: “I cannot imagine that Prabhupāda will call me back when Vāmandāsa needs so much material from me.” In a letter from 20.9.55 he writes to his disciple Vāmandāsa (Walther Eidlitz):

“I myself would never have been where I am today, if not already as a youth I doubted what people, poets, scholars said and prepared myself to learn the most strange languages, just to be able to read a text that dealt with God and the meaning of life in the original text itself and free myself from what others read into it from their mind and heart. Then, on the second day after my arrival here, my Gurudeva told me: “The first thing you have to do is to collect all what you learned, read, excerpted, felt, know. Put it in a big bag and throw it into the sea where the sea is deepest and start anew.”

Once when I felt sad, because I hadn’t been raised as a Hindu in India and didn’t have the inner associations that every Hindu has together with the concepts deva, devi, avatara, bhakti etc., he was even angry and said: “You missed nothing. It is a blessing that you did not imbibe all these associated ideas. You would have learned only wrong things. There is nothing to be learned from people, poets etc. You have to learn from God directly – i.e. what God teaches in His Own words.

Q) Who was Vāmandāsa and what is his connection to Swami Sadānanda?

The Austrian Walther Eidlitz (Vāmandāsa, 1892–1976) was a successful writer even as a youth. Some time before the outbreak of the Second World War, he felt an irresistible yearning for going to India to study its ancient religion, and went there with the intention to bring his family along later. The war interfered with these plans, however, and, as the family was Jewish, Vāmandāsa’ wife and son were forced to flee from the Nazis, and, eventually, found refuge in Sweden. Meanwhile Vāmandāsa, as an Austrian citizen in India, was interned in an Indian camp, where he met his guru, Swami Sadānanda Dasa, who in that place began his uninterrupted teaching of him. (See Eidlitz’ book Unknown India) After his release from the internment camp and before he left India for travelling to Sweden, Swami Sadānanda and Bhakti Hridaya Vana Maharaja came to Bombay to see him. Swami Vana wished to initiate him into the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava tradition and from him Vāmandāsa received his spiritual name Vimala Kṛṣṇa Vidyavinode Dasa. From his first guru, Sri, he had already got his name Vāmandāsa, and for some reason Sadānanda continued to call him so even after his initiation. A few days later, in July 1946, Vāmandāsa returned to Europe and Sweden and worked there continuously to spread the knowledge of the śāstrams, the revelation of God’s word-form, through lectures, courses and books. All this time, Sadānanda assisted him with untiring devotion by providing him with material and correcting his misconceptions. Some books (especially the German book Die Indische Gottesliebe, in Swedish Kṛṣṇas Leende) unfortunately contain many errors, because Vāmandāsa was still mixing mysticism into the teachings of pure bhakti. The later books, however, and above all his work, Kṛṣṇa Caitanya, Sein Leben und Seine Lehre (Stockholm University 1968), give a brilliant survey of the essence of śāstrika revelation.

In spite of the mistakes Vāmandāsa had made in the beginning, Sadānanda wrote in one of his last letters to him: “Tell your friends, that everything they do for you, they do for me as well.” We cannot be grateful enough to Vāmandāsa. In addition to all the books he wrote, he also brought Sadānanda to us, here in the West. By his lifetime achievement Vāmandāsa broke new ground, presenting in a European language a knowledge that at that time was practically unknown in the West.

Q) What did Swami Sadānanda do after Bhaktisiddhānta’s disappearance?

After the disappearance of his Gurudeva in January 1937, Sadānanda went on a study tour and pilgrimage all over India, from Badarīnātha, close to the Tibetan border, to Cape Comorin (Kanya Kumārī, South India). On his pilgrimage, mostly on foot, he gave many lectures at universities, colleges and monasteries, visited holy places, discussed with scholars, lived in caves with solitary sages, collected manuscripts of the Caitanya movement, was a guest at the homes of great maharajas and industrialists, but always lived as a mendicant, till he was arrested and put in an internment camp in September 1939 – due to his German citizenship.

Q) Did Swami Sadānanda ever speak about his years of prison internment in India during World War II? What events did he relate?

From his own and Vāmandāsa’ notes one can see that he suffered tremendously from being denied to practise his religion, to have vegetarian food, a secluded place for his worship etc. Nevertheless, he spent most of his time translating the śāstrams. Several times he was on the verge of death but decided to continue to live for the sake of Prabhupāda’s sevā and to assist Vāmandāsa. He writes:

“As a matter of fact, there can be no opposition against Kṛṣṇa and those who want to serve Him, but opponents are deputed by Him to give us the chance to serve Him. Outwardly I might be degraded to an outcaste, but all the denial of cult and food cannot put out the fire of Divine Prema in my heart; it is rather increasing. All possible opposition from all quarters, simply to exhaust all the possibilities to obstruct my serving temper, to give me the chance (to prove), that a mleccha (outcaste)-bhakta of Gurudeva never stops and never gives up His service.” (8.6.44)

On another occasion, on the verge of death, he tells Vāmandāsa:

“My mission this time was just this, to be born as a human being far away from India, in Europe, and in spite of countless difficulties still become Prabhupāda’s friend. He told me that we have always been together since eternity.”

Before his release, in July 1945, he writes about his hardships in his notes:

“To whomsoever it may concern The spiritual ecstasies experienced in the cult of Sri Sri Radha Govinda are of such an uncommon and extraordinary character, that though of Divine origin, the spiritual madness and intoxication appears to those who have not realised them, as symptomatic of insanity, epilepsy or lunacy. The Kṛṣṇa-dedicated souls are, therefore, instructed to hide these experiences from the view of outsiders, nay, it is considered base and low to expose any of these experiences to the view of those who are averse to the unconditional service of Sri Kṛṣṇa and indulge in the intellectual or emotional exploitation of whatever they come across in their so-called human life, which is – in reality – only another form of bestial life – being void of the true meaning of life: to serve God unreservedly and unconditionally. […]

It was the order given to me by my Divine Master that I should devote all energy I can spend to the study, exposition, translation and explanation of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam and Sri Caitanya-caritāmṛtam. The hostile attitude of the authorities and the cointernees in the wings towards a “renegade” of European civilisation, the complete failure to instinctively apprehend the real nature of myself and the purpose of my life made it advisable to adopt every means to pretend to be a sahib and European. I know it for definitely that had I strictly adhered to the principles of my cult, i.e. strict Hindu-diet, dissociation from atheists and non-Vaiṣṇavas and insisted on the exercise of my cult and worship, the authorities would have been pleased to send me to a lunatic asylum to get cured of the religious frenzies. I did not care for the opinion of others but was eager to adopt any means to keep the body physically fit to provide the strength at least for a few hours of study and translation of the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam. […] Besides, wherever I was, I tried by a sort of mimicry to adjust myself to the ways of my surroundings to have the chance to come in contact with other internees for the purpose of clearing the misunderstandings about religion in general and Kṛṣṇa-cult in special (Sanskrit and philosophy classes to the Christian missionaries, priests; lectures etc.). […]

To an outsider this appears as inconsequence – but what else could be done. To insist on my cult and diet – was the way of a troublemaker, “let him die if he is so foolish and fanatic” – and when apparently I followed the advice – “you adjust yourself to the camp life” – I was criticized for not being sincere in my religion, being a fake sādhu. It is time now to bring home to the intolerant mind of the authorities and cointernees that I am not a fake sādhu but a fake sahib. […] To my own conscience I have fulfilled my task as an eternal servant of Kṛṣṇa and Prabhupāda, born in a European body. I am glad that I was spared no difficulty and trouble, because it fostered my will to find new and new ways to serve Him.”

Being released, but now afraid of being expelled from India, he writes:

“In the dark hours, when it appears to me, that the pangs of separation from those who love Kṛṣṇa – for whose service I came to India – are unbearable, I have repeated visions of living in overcrowded quarters amidst the scorching blazing heat of a fire consuming the small buildings around me. My tongue is parched and I feel suffocated. So far I’ve had the strength to overcome the depressions, vanishing like thin transparent evening clouds before the waxing moon of my hopes.

Now I visualise the hopeless nights with heavy layers of clouds, overcasting the sky without even the chance to catch one ray of the waning moon. I visualise the day when I will be asked as one in a flock of cattle to leave the country in which I was living in the loving service of my beloved Gurudeva earlier in my life. Because others, not myself, identify my real person with the perishable covering of flesh and bones, called a German individual. Perhaps it was not practical, considered from the point of view of sound common sense, to agree to the play of identifying myself sometimes with something I was not. Yet, this was the only chance to try to carry to others, occasionally at least, the outside cover of the exoteric mysteries of the art of love for Kṛṣṇa. I apprehend the day when I will know for certain not to be fortunate to bow down to the samadhi of my beloved Master or to touch the lotus feet of the few great souls left on this earth from all entourage.

I feel if I would concede to relax for a little moment, my energy and will power utilized to the last to keep this physical and mental organism running, it would vanish as water from the open hand. Should it be really worthwhile the effort to try to make this body proceed to a country where I have to miss the invigorating rays emanating from the spiritual soil of India, cut off completely from the chance to support myself by the verbal vibrations of real bhaktas, to live after years of internment again alone with no one to talk to or exchange thoughts and experiences, without the many forms and things in this country which awaken associations with Kṛṣṇa and His descents? Oscillating between the two alternatives of proceeding to a desert or leaving this body to the care of Mother Bharata Bhumi, I cannot make up my mind, and trust Prabhupāda and Kṛṣṇa will decide and make me realize the decision soon and unexpectedly.”

Q) What did Swami Sadānanda do after his years of prison internment?

With Swami Vana’s help he got released and went to Vṛndāvana. He also went on some tours together with Swami Vana but most of the time he was very ill. In May 1946, he writes in a letter to Vāmandāsa:

“I spent some time in the hospital of the school of Tropical Medicine in Calcutta, but as a result of all investigations and X-rays and what not else, it is certain that I shall never be healthy in my life but remain permanently invalid. I left the hospital and decided to follow Vana Maharaja and accept the invitation of some bhaktas in Assam where I have never been before and to visit some of the ancient Shrines in the land of Tantra. After that I shall return to Vṛndāvana which I feel is the centre for my own religious life. I shall try to found an institution of my own in case I can get some relief from the bad physical pain from which I am suffering constantly.” (Gauhati, May 3, 1946)

Not much is known about what happened to Sadānanda during the following years. One has to keep in mind that it were turbulent times in India then: 1949 it was declared a republic, then it was divided into India and Pakistan, resulting in heavy religious conflicts and one million people dead. But after things had settled down a bit, in November 1950, Vāmandāsa returned to India from Sweden – where he had found a place of refuge after his release from the internment camp in 1946 – and spent five months together with Sadānanda in Māyāpura, Purī, Mathurā-Vṛndāvana and Benares.

After this period Sadānanda mostly stayed at a poor friend’s house in Howrah, Calcutta, most of the time bedridden. From now on, and for ten years, he tried to gather strength to go to his friends in Sweden, who regularly sent him money for his survival. During these years he worked constantly with his translations of the śāstrams, sending new material to his friends in Sweden and especially to Vāmandāsa, for his books, lectures and courses in Europe. But to his great disappointment, he gradually realized that Vāmandāsa could not pass on the teachings he had received from him in its pure form. Still, he continued to help him, even sending him hundreds of pages of corrections to his second book, Indische Gottesliebe, published in German and Swedish in 1955.

In February 1953, Sadānanda’s bhakta-friend in Howrah, Gauranga Ghosh, wrote to Vāmandāsa:

“You know with great, great difficulties all of us here tried our best to snatch him from the hands of Yama. You cannot imagine how his condition was since September: severe pain, his head getting cold all of a sudden during day or night. Doctors, injections, protein, medicines from Canada, careful diets at tremendous cost somehow made him get to read. All of a sudden he decide to start on Murāri’s notes. He went to a house of a man not far away from here only to sit there all the nights till dawn and write and think and write, and finishing Murāri’s notes he was quite finished himself, as in that house there was nobody to look after him, to give him diets and medicines at hourly intervals as advised. When your manuscript came, he worked like mad night and day and did not listen to anybody. The day after it was dispatched he collapsed and with great difficulties he was brought back to my house. We nurse him by turns, but you know we can give only our time and strength and love for him.”

Q) When did Swami Sadānanda return to Europe from India?

In 1961. A small group of Swiss had realised Sadānanda’s deteriorating state of health under the deplorable living conditions in Calcutta and offered him a flight to Basel. In Basel an oral surgery operation healed his fever that had lasted for many years and – in combination with other tropical diseases and several failed surgeries in the internment camp – had often brought him to the verge of death. In the following he lived in Basel and payed periodical visits to Sweden in the summers.

Q) Did you ever meet Swami Sadānanda personally?

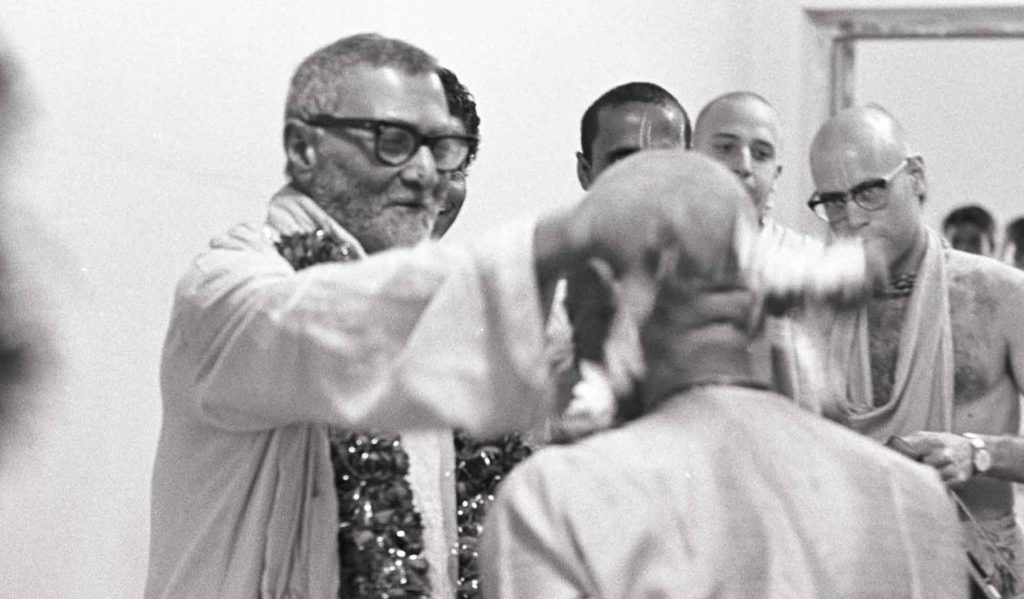

I only met him a few times before his disappearance in 1977 but these meetings changed my life thoroughly. His outer dress and behaviour didn’t reveal anything extraordinary – on the contrary. But my distinct feeling was that he was not of this world and that he could read every secret thought I had. On one occasion I spent a few days with him together with his disciple Vāmandāsa (Walther Eidlitz) and I was appalled at seeing 80-year-old Vāmandāsa turn into a 5-year-old boy in the presence of his much younger Gurudeva. Hard as a thunderbolt, and for two days, Sadānanda criticized him severely for the many mistakes he had done in his translations of the śāstrams etc.

Before, in Vāmandāsa’ book Unknown India I had read that Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura also often expressed what Sadānanda called ‘aggressive grace’. Many years earlier, in the internment camp in India, Vāmandāsa had asked Sadānanda:

“Why do they torment you? Give you the worst place in Wing II, without air and light, spread lies about you, that you once again act as a troublemaker. As if they want to catch you in a net. – To get out the extreme of sevā. Yes – Yogamāyā [God’s Own, internal śakti, attracting towards the Centre of all existence]. She behaves like vikarṣaṇa-śakti [the external śakti, Mahāmāyā’s repelling force, hurling away from the Centre of all existence]. – And why do people hate you? It seems that your methods of “aggressive grace” fall back on you as karma. – Aggressive grace is ahaituki [causeless]. – You mean cit, without karma? – Yes. – And why do they hate you? – Because they feel that I am firmly rooted in something. This is what the philistine hates most of all, when someone is firmly rooted, as he is not, “he is drifting”. (Notebook of Vāmandāsa)

On the day of our departure Sadānanda’s mood changed and he embraced both Vāmandāsa and me heartily, with tears in his eyes, expressing a kind of affection I had never experienced before. Then I knew what the words qualifying the guru meant: “Hard as a thunderbolt, soft as a flower.” 20 years earlier, Sadānanda wrote to Vāmandāsa:

“You must not be unpleasantly affected by my severe criticism of your faults. It is because I love you so deeply, Vāmandāsa, for your absorption in the bhakti cult, that I allow myself to be so hard on you, who has sacrificed so much for me. But you may rest assured that your sacrifices will not stay by me; they go like sunshine through wide-open windows to Him and Her.” (Letter 19.7.52)

The day before, he also showed me his great sense of humour when I suddenly, out of gratitude felt the need to kneel in front of him. Then he looked at me with a smile, saying: “Have you got some pain in your back?”. Then, when he emphasised the utmost importance of sambandha-jñānam and defined the ātmā and the subtle and gross body, he suddenly asked me, his eyes flashing:

“Do you know the meaning of the word ‘Radha’? It is derived from the two Sanskrit roots ‘rā’ and ‘dhā’. ‘Rā’ means ‘to give’; like a flash of lightning Rādhā grants Kṛṣṇa, the deep, dark mystery, insight into His own being – and then She immediately withdraws again, removes Herself, ‘dhā’.”

Q) What was Swami Sadānanda’s demeanour/character and what did he stress as the most important message of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism?

He was very hard on himself but extremely tolerant and understanding when it came to others. In a letter to Mario Windisch, February 25, 1968, Bhaktivedānta Swami writes about Sadānanda:

“In Bombay sometimes we lived together and he used to treat my little sons very kindly. His heart is so soft, as soft as a good mother’s, and I always remember him and shall continue to do so.”

Still, Sadānanda could not stand distortions of the bhakti philosophy. This made him very upset.

“Regarding the universality of the message of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism he writes to Vāmandāsa: You must not forget that Eternal Power, wherever it is at work in the world, is expressed in the images of thought of the prevailing time and culture. To really be able to gain a factual and positive value from Vāmandāsa’ lectures and bring it into one’s own life, one must try to look through the seemingly Indian attire and see the essence – for true Knowledge is conveyed to mankind and is never Indian, Asian, European or African.” (19.6.61)

But he was clearly aware of the difficulties:

“Mr. A. is of the opinion that “Sweden is too small for Sadānanda”. – Tell him that the world is too small for me. I might find two or three people in a whole continent, who can understand what rasa is and who are able to appreciate a work of rasika as the Bhāgavatam or Caitanya-caritāmṛtam. Here in India there might be two or three persons?

To me it is as for Aṅgirā Muni in Bhāgavatam VI. He came to Citraketu and wanted to offer him the highest gift there is – but found him longing for descendents. Everyone longs for something else, not for inner freedom. Everyone wants to remain slaves, just change clothes and chains, no one wants to cast them aside.” (Letter to Vāmandāsa 1960)

Bhakti is difficult, the individual is completely alone with God and it is very, very difficult for one – even if he had a guru – to actually practise bhakti in the West, i.e. to sense what is chit behind the veil of the seemingly Indian appearance and covering (externally and linguistically). 99,9 % of those who listen to you and read your books while they search will cool down after their fi rst enthusiasm and go on searching somewhere else. People want to bring themselves, the concrete man himself, into bhakti – man, whose worthlessness they are unable to realize, because they don’t know and experience anything else than what they daily and since millions of lives before have known and experienced as their ‘I’.

Even Mahāprabhu and His Own co-players came to a deadlock – when no one else was eligible to receive bhakti. Not to expect anything, not even physical and mental “shanti”, inner peace, in one’s heart of hearts, as God’s gift in return for our efforts – this is only for those few who are the noblest of the noble. […] Haven’t I myself, before the war, given lectures, explained the śāstrams? Thousands – and except a few, has anyone been able to make a 180° turn from self-centredness to God-centredness? And yet, those two or three are worth the effort. (8.11.59)

He also stresses that the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava sampradāya is the only tradition that acknowledges the śāstrams en masse, which gives their full import:

“Mahāprabhu did not create any new system, nor did Jiva Gosvāmī. Acintya-bhedābheda is a conclusion, a siddhānta, the conclusion drawn regarding the Revelation. When the Upaniṣads talk about unity and duality, distinction and non-distinction, and with this double statement want to make a statement about God’s nature, it follows that God simultaneously is form and not form, one and manifold etc. This may be contrary to the laws of human logic, but God and His nature are in no way confined to obey mundane, human laws of thinking. The word acintya-bhedābheda-vāda appears only later. Mahāprabhu and His contemporaries had no intention whatsoever to create a new system in addition to the existing opposition between the monistic and dualistic systems, but wanted to show that one does violence to the Absolute, when one tries to squeeze it either into the systems of monism or dualism, and instead of accepting the double statements of the Revelation only adhere to one side of it.” (Gauḍīya-Sampradāya-Tattva, notebook Māyāpura 1959)

- Q) What do you consider the most important among the writings of Swami Sadānanda?

Sadānanda never published anything himself, saying that Vāmandāsa’ writings were for the public, his writings for the few. He devoted most of his time to translate the śāstrams into German and then dictated them to his friends. These dictated and typed texts from some of the main Sanskrit and Bengali sources will gradually be checked and translated into English and hopefully published in the future. Personally, I consider his corrections to Vāmandāsa’ second book Die Indische Gottesliebe most important, because it goes to the bottom with all possible kinds of misconceptions we all might have in the beginning. Reading it on a regular basis is a training to redirect our mind from being self-centred to becoming sevā-centred. One cannot ever train this enough. From Sadānanda’s own point of view, at a certain time in India, the Caitanya-bhāgavata seems to have been of utmost importance to him. He writes to Vāmandāsa (6.8.1955):

“Everything which you have read so far about Caitanya Deva – from sources and books – is reduced to a pale reflection before the effulgent moon of this work. Believe me, without this work you cannot have any idea what līlā is, especially with His Own. This is no exaggeration. […] It presents the complete theology of Caitanya-līlā, but by way of telling the events of His life, not theoretically. I have translated word by word, technical expressions in parentheses. It may well be my testament. With the Caitanya- bhāgavata it all started when I arrived in India – should it be the close, too?[…] This work is as much revolting to the Indian general religiosity of the past as of the present. He and His Own are no humans; They come and go, become visible in time and space and become invisible into the realm beyond time and space (Vaikuṇṭha) again, which is omnipresent, only not perceptible directly, as long as the highest level of Knowledge and Love (bhakti) is not attained. You are my true child, Vāmandāsa. For your sake I have translated this work the last days. You must not mix things and present/ think a sickly sweet Caitanya.”

Q) In what countries did Swami Sadānanda preach in Europe and during what years? What type of programs did he have?

He wanted to stay in the background and let Vāmandāsa meet the public. Vāmandāsa wrote books, gave lectures in Sweden, Germany and Switzerland and had summer courses in Sweden. Sadānanda himself mainly focussed on his translations and dictating them to his disciples and friends.

Q) How many persons came to Swami Sadānanda in Europe to become his disciples?

Only a few who met Vāmandāsa came to Sadānanda. It is hard to say, but maybe he didn’t give initiation to more than a dozen during his lifetime, in India and Europe. But some others, who only met him briefly, now consider him to be their śikṣā-guru, by listening to his vāṇī in his texts, as well as others who never met him in person.

Q) What was Swami Sadānanda’s view of Christianity or Western religion in general?

He followed his guru’s view that Christ was a śaktyāveśa-avatāra, a great human who is permeated by Viṣṇu’s śakti and knows himself to be God’s servant or son. In a letter from 15.03.54 he assures that:

“We have no reason to doubt that actual and real Christ – not what is going on to be given as ‘Christ’ – is the way to God the Father. In relation to Him we are like children, but this father-children relation is only one of the possible forms of relation the soul can have to Him, and it implies the great danger to look at Him as the Divine Order Supplier or Department-Store Director to whom we may appeal for redress of our moral, intellectual, physical or spiritual wants and needs.

Christ has not given replies to the most burning problems of our soul and relation to God, because possibly, this was not needed or intended by this form of Divine Descent. Christian mystics have tried to express higher individual forms of their own realisations with the vocabulary of Christianity – but actual and real revelation expresses itself in Words and Ideas and they appear too meagre and lifeless in these mystics. Had they come in contact with Hindu śāstrams and not late classical philosophy they might have found more encouragement and scope.”

Yet he was working on a manuscript about the religions and philosophies of the world, calling the latter in total an aberration compared to Vaiṣṇavism:

“In this manuscript will be explained, beginning with Mose to Nietzsche and Marx, from Christ to Mohammed and Buddha till the “Weiße-Käse-Apostel” [“cottage-cheese-apostle”, Joseph Weißenberg, 1855–1941] and Anthroposophy, that everything, really everything is an aberration and that even the best of it is only a portico to what the Karma-khāṇḍa parts of the Ṛg Veda start with. The manuscript will please nobody; it is straight and hard as the Gita and Bhāgavatam XI are. The manuscript is directed towards those, who are in doubt about their religion and ask, not towards those who already have decided against a God, who is not tailored to man’s needs. To those He grants, via His Māyā, unwavering faith in what does not lead to the goal.” (Gītā 7,20–23)

He pointed out that –

“The Western or Christian conception of world and man cannot be the basis to understand bhakti. Virtue and sin are relative terms, concerning the false ego of man. The ātmā by constitution belongs to the cit-realm, but as he is an atom of cit only, he requires cit-śakti to realise His and his nature. Bhakti is the śakti to know and to love. As soon as this śakti is given, the ātmā becomes mukta in the original sense. He does then everything from His point of view, not from the ātmā’s or much less from the point of view of the present ego.”

And in his corrections to Vāmandāsa’ book Indische Gottesliebe he writes:

“Already for that reason – the fact that the religions outside the Vedic Word Revelation have no clear conception of the most basic principles, not even the nature of the ātmā, God’s form etc. – can the indistinct stammering of these religions on no account lead to God, at the very most, some time in a later life, be a preparation for listening to what real Revelation is and learn what the Divine Sun of Wisdom is compared to the mystic, smoking oil lamp.”

As a model of how to present Vaiṣṇavism to the West he named the first introduction of Buddhism as a positive example:

“The classical Buddhism, e.g., was first presented in this manner to the West and quite objective accounts, not tied to any personality, have helped many westerners to sincerely worship and love Buddha, without externally forming a new cult, without forcing an external dramatic “conversion”. When Buddhistic groups were formed it already went wrong; and where attempts were made to bring East and West closer in the “form” of Western philosophy or comparisons with Christian theology etc. (Otto, Deussen, Dr. Radha Kṛṣṇan), all went wrong.”

Q) What did Swami Sadānanda consider as his task in regard to his friends in the West?

In a letter to Vāmandāsa 12.11.54 he writes:

“Nirguṇa-bhakti has nothing to do with the Indian, the Eastern, it is beyond every human emotion, every soul, Eastern or Western. Bhāgavatam and bhakti imply something completely un-Indian. Being able to appreciate them requires a complete break with the Indian and Western. […] First of all, you must give yourself and the people a clear, distinct “psychology” and “philosophy” – as a foundation. You are not Mahāprabhu who by His mere command “say Kṛṣṇa!” granted the ātmā’s bhakti-śakti, so that the disciples immediately grasped and could discern what the ātmā, the cittam, the world, God, Brahma and Kṛṣṇa and their mutual relation is. If nothing but “Hare Kṛṣṇa etc.” was enough, then there hadn’t been any need for Śuka to instruct Parikṣit in the philosophy of the Bhāgavatam etc. for 7 days and nights!”

17.10.55 he writes:

“The correct approach to the Life and Teachings of both Sri Kṛṣṇa and Caitanya Mahaprabhu depends on the correct understanding of some fundamental principles of what is called śāstrams. śāstrams do not mean ‘Scriptures’ but that which is meant to guide – and if necessary – “chastise” man’s intellect when he intends to approach Divinity.[…] I feel I shall write for all of you what I myself would have needed when I came to India first and tried to understand the Bhāgavatam but there was nobody to get me a correct guide as to what to forget and what to keep in mind when starting for a spiritual life under the guidance of Caitanya Deva. So that others who like myself want to go that path may have less difficulties than I had, I give a short summary of what expects us and from what ideas we have to separate us – how dear they might be to our heart – if we desire to grasp a bit of the mystery of the Bhāgavatam. Please, there is nothing like ‘mysticism’ in the śāstrams, everything relating to the world, the ātmā and God, so far He is concerned with the world is terribly clear and leaves no place for a groping in the dark and indistinct sentimental complexes.”

And a few years later:

“It’s all about those noble-spirited ones, who are able to tread the most glorious path in this age of discord, – as a consequence of their service during former lives – and to collect those; and secondly, for the future, in words and writings establish that there are such glorious, great Divine things, completely different from what man expects and senses, to help those like Sadānanda to be able to truly perceive the highest truth.” (Letter to Vāmandāsa 1959)

Thank you very much! Gaura Haribol!

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.