Overview

In "Anādi (For Advanced Philosophers" Śrīla Śrīdhara Deva Gosvāmī Mahārāja gives a synopsis of how the jīvātmā appears in this material world and explains the true meaning of the word anādi (beginningless).

Consciousness means to be endowed with free will. Without free will no consciousness can be conceived. Consciousness means free will. This individual point of consciousness (jīva) means very meagre free will. By the exercise of his free will the jīva is asserting itself. It may go that side (Vaikuṇṭha), or this side (the land of exploitation). Some jīvas are going that side; some are coming this side from the marginal plane.

Free will is the first action of coming into the land of exploitation. It is by free choice. Svabhāva, or independence, is already there in the jīva – the very nature is there. But as the resulting consequence, we see that some jīvas have taken their chance on this side. They did not accept submission, but wanted to dominate. With this germinal idea of domination, the jīva enters into the world of exploitation. The consequence of exploitation is added to his free will, then that is the basis of all these developments in variegated nature. The original starting point is like that — the vulnerability of the free thinkers. Free thinking is vulnerable because it is very meagre, small, anu-caitanya, anu-svairiatva – limited freedom, limitation of free will. That is the cause of this world.

Māyā is automatically the effect of the outcome of the vulnerable free will of the jīva. The world exists, just as the prison house exists due to evil desires for the encroachment on another’s property. If that misdeed is absent, then the prison house is absent. Prison houses are necessary. Kārā-kartṛ – Durgā Devī is kārā-kartṛ. It is mentioned in Brahma-saṁhitā, chāyeva yasya bhuvanāni vibharti durgā. Kārā-kartṛ – prison keeper. Why prison? There are prisons because there is vulnerability in the choice of freedom, leading to encroachment on another’s property. Otherwise no world is necessary. But because it is possible, prison houses are there. If disease is absent, hospitals are absent. No disease — no hospital. No crime — no prison house. No misuse of free will – no world!

No blame for the existence of this world or our suffering should be put on the shoulders of Kṛṣṇa, nor on Māyā. You and you alone are responsible for your own suffering. You are weak — your thinking, your capacity, your everything is weak.

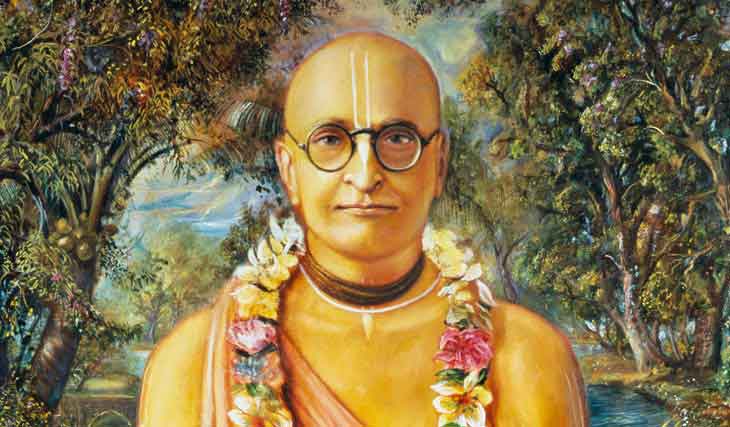

Once in Purī, one gentleman came to our Guru Maharaja, Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda, and put a question, “How did our life in bondage begin? How it first started? Who is responsible – God, Māyā, or jīva? There are three factors –God is there with His paramount power, Māyā is there which comes to capture the jīva, and the jīva is independent we are told. Then how did it begin? What was the first cause of such a beginning – the jīva’s contact with the world? The jīva is free, and God is, of course, absolutely free and Māyā is there. Māyā is playing with us. But when it first starts, who is responsible?”

Then Prabhupāda answered but that gentleman couldn’t follow what he was saying. In various ways the gentleman was pushing his question and Prabhupāda was very much feeling disturbance. A few other persons from our matha including Professor Sanyāl, Vāsudeva Prabhu and Hayagrīva Prabhu were also present. I could not tolerate this, so I offered obeisances to Prabhupāda and asked his permission that. “He cannot follow your urgent statements, so please order me to answer his question.” Then Prabhupāda happily said, “Yes, you may talk with him.”

I told that man, “One by one let us analyse. Suppose if for the pleasure of God, God is the cause – then what is the next step? What it will be? The jīva is suffering from misery, and God is the cause of the suffering of the jīva – can you adjust it? He is omniscient, He is omnipotent, He is all-benevolent and He is the cause of such suffering? He is seeing the fun, and so many jīvas, they are under misery, suffering like anything. He can deliver them also, but He does not do so. Can you accept that conception of Godhead?”

The gentleman replied, “No I can’t.”

“Then He cannot be the cause of the suffering of the jīvas.”

The gentleman agreed, “Yes.”

“Then if Māyā is the cause, so many other questions come. Is Māyā more powerful than the jīva and God? Māyā is torturing the jīva and the omniscient God is seeing the fun. Then there is no justice in the world. God is aloof and Māyā is attacking and torturing the jīva. Is that the position of God?”

Then a few other steps also I explained, “The sufferer is responsible for his own suffering. If we leave the responsibility on the shoulders of Māyā, these are the difficulties – on the shoulders of God, these are the difficulties. The cause of the suffering of the jīva, of the soul, must be within him (the jīva). It begins in this way – first it starts with free will. In the beginning it is like that of curiosity and then when you connect once with Māyā, then Māyā gets some influence over you. In this way, God does not come to interfere with the freedom of the soul.

Consciousness means endowed with freedom. But the jīva is a particle of consciousness, so his freedom is also a particle. The vulnerability of the free will of the jīva soul is the cause, the first starting point. Then Māyā comes. Just as when one begins taking any intoxication – first it starts with something like curiosity, and then the intoxication gets some position, some impulse is created, momentum, then he loses his freedom. The free will of the jīva gradually comes into the clutches of Māyā losing it’s own free choice. Then that gentleman admitted, “It is true.”

Free will is there and that is the rub. Some say in disappointment, “Why has Kṛṣṇa given such dangerous free will to us, by misusing which we are under eternal suffering? Why has He given? He is omniscient – He is all-knowing. Then knowingly we can misuse. Why He has given such a thing to us? Why has an adult given a dagger in the hand of an infant, that he may stab himself?”

However, devoid of free will, the jīva is only a material thing. Free will is very valuable and with the help of that, the jīva can taste rasa. The tongue has been given to taste sweet also, not only bitter things. If the tongue is devoid of taste, then also he will not be able to experience sweetness at any time. Because we are only touching bitter things to the tongue, we are abusing the Creator, “Why has He given us the tongue and we are tasting these bitter things?” But at the same time, to taste sweet things the tongue is necessary.

In the service of Kṛṣṇa, free will is necessary – for the serving purpose of the Lord. Temporarily coming in connection with bitter things, we shall abuse the Creator, “Why has He given?” Some bad things are disturbing my ears, so should we think that the ears should be abolished? The eyes should be abolished because I have to see some undesirable sight? Because the eyes have been given, then the prospect is that we will have to see such charming beauty. If eyesight is withdrawn, then we are left as a stone. So free will is the very gist of everything. If that is snatched away, then we are reduced to stone. That is not desirable to anyone. Everything has got its bright side, and for that it has been created, it has been given to us. By misuse of free will we suffer, and by good use we thrive.

Some are coming into the world of exploitation to suffer, some to the world of dedication to thrive. And the beginning should be attributed to the innate tendency of the jīva, his innate nature, which is endowed with free will, free choice.

na kartṛtvaṁ na karmāṇi lokasya sṛjati prabhuḥ

na karma-phala-saṁyogaṁ svabhāvas tu pravartate

“The Absolute Truth does not create anyone’s sense of proprietorship, one’s actions or the results of those actions. All this is enacted by the modes of material nature.” (Gītā 5.14)

It is substantiated in the Bhagavad-gītā that the jīva is responsible for entering into the land of exploitation. The first awakening of freedom, free will, is from the non-specified position when the jīvas are all jumbled together — undifferentiated character, glowing only (brahma-jyoti), they are coming with free will. By free choice they are going this side and that side.

Otherwise Kṛṣṇa will be responsible for their distressed condition. But, in this verse (na kartṛtvaṁ na karmāṇi…) Kṛṣṇa says, “I am not responsible for the activities of the jīva. I have given them freedom, and they are working freely. And the clash between them is the cause of their disturbance. But when they leave their wholesale attention to their social activity and come to Me, they will get relief from all.”

The jīva’s own innate nature is responsible for that condition. The first awakening of the jīva is free will and free choice. Free means they can go this side and that side. Because the jīva is very tiny, anukta-prayukta, his free will is also not perfect. We have free choice. The result of that free choice is that some came this way, some went that side. It is unintelligible that Kṛṣṇa is responsible for the jīva’s suffering. The responsibility is with the jīva because freedom is given to him.

Someone may say that, svarūpe sabāra haya golokete sthiti – in the innermost existence we all have connection with Kṛṣṇa, but that is not true about the section that comes from the taṭasthā-śakti. Kara sarvani bhutani, kuthashto ‘kara uchyate –all the jīvas come from a particular potency of the Lord which is known as taṭasthā. Mahāprabhu says:

jīvera svarūpa haya kṛṣṇera nitya-dāsa

kṛṣṇera taṭasthā-śakti bhedābheda-prakāśa

“The constitutional position of the jīva is to be the eternal servant of Kṛṣṇa. He is the marginal potency of Kṛṣṇa and simultaneously different and non-different from Him.” (Cc. Madhya-līlā 20.108)

The internal potency is already going on smoothly, eternally, in svarūpa-śakti – Vaikuṇṭha, and Goloka. And the marginal potency is the mother of so many jīvas that come here by the wrong exercise of their freedom. But there is adaptability within. Just as while he is in the marginal potency, in the buffer state, he can come this side, he can come that side also. The jīva has got his adaptability with both sides. He is not in Goloka – he has not fell from there – but he has got his internal adaptability to come in favourable circumstances, then he will bloom to fruit and attain that position.

Free service is necessary, not forced labour. Devotion is not forced labor, but devotion is voluntary service. The jīva soul will be happy when freedom is there, but he cannot feel satisfaction if he is forced into service. Devotion is free cooperation and free service, and forced labor is not devotion nor is it service, nor is it dedication. By the nature of things, Kṛṣṇa cannot interfere and He does not interfere. Not even God, what to speak of His devotees, will interfere with the free will of the jīva soul. Freedom is indispensable for the soul and it cannot be snatched away.

Freedom does not mean absolute freedom. Because the soul’s existence is small, his freedom is defective – there is the possibility of committing a mistake. Freedom of the minute soul does not mean perfect freedom. Complete freedom would be perfect reality, but the minute soul is endowed with the smallest atomic freedom. This is the position of the atoms of consciousness, and this is why they are vulnerable. They may judge properly or improperly; that is the position of those who are situated in the marginal position. If the soul were not endowed with the freedom to determine his position, we would have to blame God for our suffering. But we cannot blame God. The starting point of the soul’s suffering is within himself.

This is in the clear introspection of the sādhaka. The very subtle-most thing, the starting point, cannot be detected by ordinary consciousness. The participation of the soul in this material world has been called anādi – that which has no beginning, because it affects before he enters into the factor of time and space – jaḍīya-kāla. But one can see that this is limited. However lengthy it may seem to the victims of Māyā, still it is a limited thing.

The jīva’s connection with this māyika world is called anādi. Anādi means beginningless. But anādi has been explained in this way – why is it anādi? Because after he enters this phenomenal world, then he comes within the factor of space and time. Space begins – time begins. It is conditional. The time calculation of the world only begins when we enter the māyika ego and we come within the form of thought. Time, space, person – these are the forms of thought and they come from ego – this ego of the non-eternal aspect, the phenomenal aspect.

Everything in its innate nature has got a real connection with the Lord. The inner thing is more important than the outer impressions so that must be given preference. We must think in that way. Then we can find that this māyika existence is temporary, though it is told anādi. Anādi means before it enters this world of mundane thinking, the primal stage of conscious existence. So, although it is told as anādi (beginningless), still it has got ādi (a beginning) in the spiritual record.

From a plain sheet of uniform consciousness, when specifications begin, movement begins and then individual conscious units grow. Because it is conscious, it is endowed with free will, and by free choice from the buffer position, from the marginal position, they have to take one side – the side of exploitation, or the side of dedication. By exercise of their free will they start, and as a result we see that some come towards exploitation and some go towards dedication. If we are to analyse to the extreme, then we are to follow such a train of thought. Anādi bahira–mukha. Anādi means that which has no beginning. Then why after they enter the land of exploitation, do they begin to come within the form of thought, place and time? Before time, before the conception of this material time, there is movement – so anādi. Firstly, bahira-mukhata means the tendency towards exploitation. At the beginning, the first tendency is towards exploitation. When jīvas enter the area of exploitation, then that comes within the factor of time and space, the thought of the mundane world. So it is said, anādi bahira-mukha. Some enter this side and some may go towards Vaikuṇṭha. In this way, the equilibrium is disturbed and the dynamic character of this world begins in the negative side.

The jīva has got his beginning, but does not come within the jurisdiction of the world of limitation until he exercises his free will. Out of curiosity he first enters into this land. From then he comes under the factor of this limited world. His participation is beyond the beginning of this limited world. Therefore, it is said, anādi. Anādi means does not come within the jurisdiction of this limited world. First participation begins, then entrance into the world of consideration. First there is subtle participation and then the jīva comes within calculation. Mundane calculation is not possible within the eternal world. The jīva comes within the jurisdiction of mundane calculation after subtle participation. The jīva’s beginning is before. Anādi – before this finite relativity.

It is a very intricate question – troublesome, intricate and puzzling. The nature of too much discussion may oppose faith. Ultimately, everything is adhokṣaja. Kṛṣṇa, Nārāyaṇa – that is adhokṣaja. We must have some respect for that and it is approachable only through faith – śraddhā, and not by intellectual reason or argument. The solution is not within our mental scope. Mahāprabhu says acintya. It is not within the bound of your intellect.

So when we are discussing things it should be only to understand the śrauta siddhānta (conclusions heard from the previous ācāryas), the positive thing that has been given to us. We may try our best to use our experience to know the wholesale character of it, but too much of this will disturb our faith. The possibility is there. We must always keep it in the background of our discussion – that His ways are unknown and unknowable; we cannot bring Him within our fist.

Related Articles

- The Insanity of Inquiry by Śrīla Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Deva Gosvāmī

- Anādi (For Advanced Philosophers) by Śrīla Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Deva Gosvāmī

- Inconceivable Topics by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Love of God is Dormant in the Heart of the Jīva by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Jīvas and the Marginal Plane by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- The Blame Game by Gaura Gopāla Dāsa

- Jivera Dayā (Mercy to the Living Entities) by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

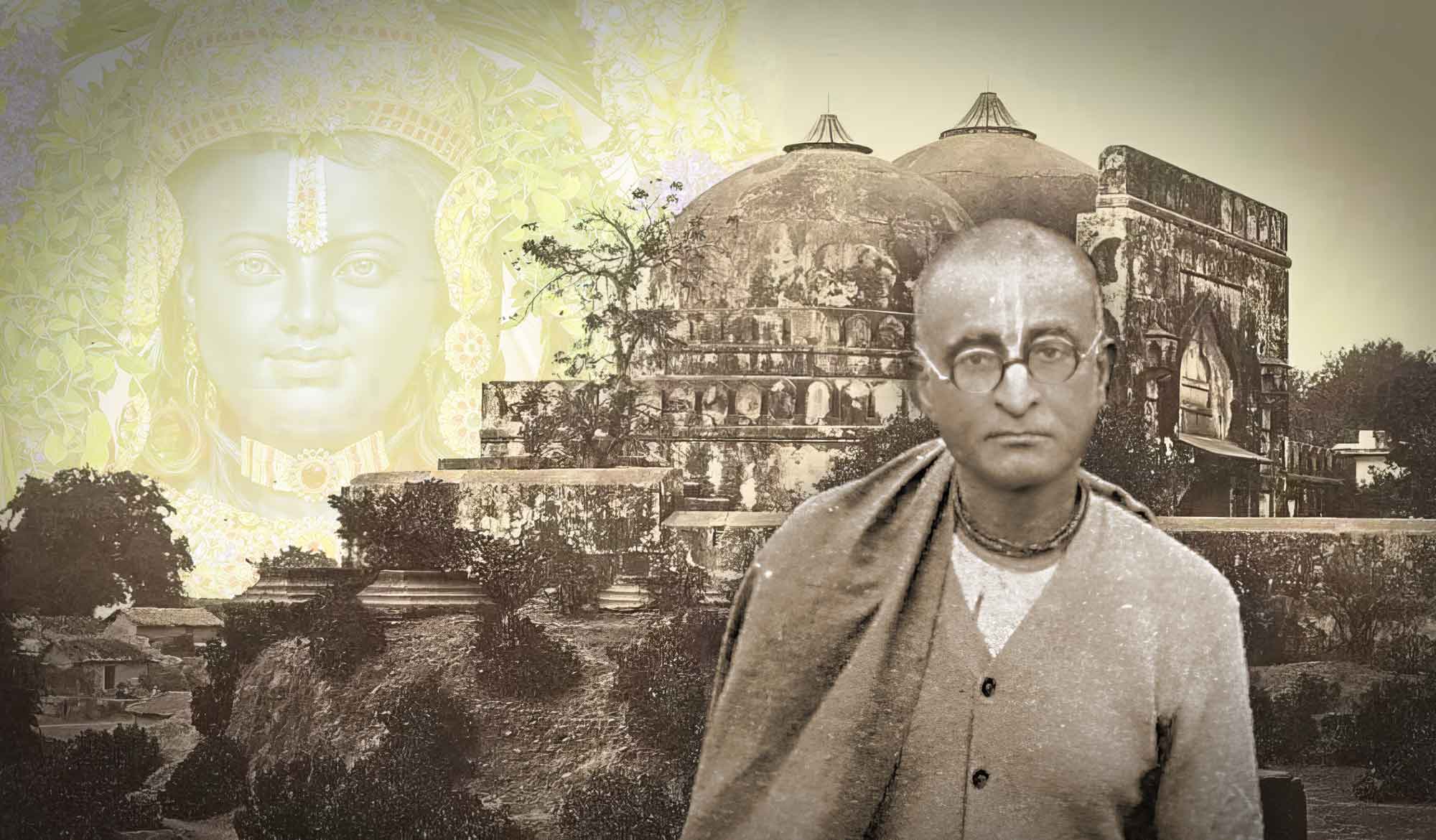

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.