Overview

In 'Zarathustra and The De-evolution of Theism' Kalki Dāsa narrates the ancient Purāṇika story of Jaraśastra of India and how he brought monotheism to the west through his new religion which became known as Zoroastrianism. Kalki also shows correlations between Zoroastrianism and the other Abrahamic religions.

Thousands of years before the Abrahamic religions emerged in the Middle East, ancient India was home to an advanced civilisation characterised by its art, science, culture, and philosophy. Most notably, the Indians understood that one Supreme Being was the source of everything, beyond any law, and existing before the onslaught of time.

The ancient Indians were experts at preserving wisdom, and they did this through a strict discipline of hearing from the spiritual master (guru), and repeating that message without adulteration. How that knowledge is presented has been adjusted throughout the ages, but the message has not changed.

In ancient times, as well as at present, people invent their own philosophies independent of the revealed truth. They do this in order to attain a reputation of being a ‘wise man’, as well as the prestige of accumulating followers. Members of the ancient Vedic culture, however, did not tolerate this sort of behaviour and expelled such people from their borders.

In the Vedas we find the story of a person named Jaraśastra who was the half-brother of the sage Vasiṣṭha Muni. He invented his own philosophy and challenged Vasiṣṭha to a debate. Vasiṣṭha defeated his brother, and as a result Jaraśastra was forced to leave Bharata-varṣa (ancient India). He eventually settled in Persia, where the desert-dwelling people of that area accepted his religion.

The Purāṇas also mention the origins of Jaraśastra. Nikṣubhā, the daughter of a sage, was engaged to marry Agni, the god of fire. During the engagement she had an intimate affair with Mitra, the sun god. Hearing this news, Agni became enraged, and cursed their son, Jaraśastra, to be born as a heretic. (The name Jaraśastra in Sanskrit means ‘heretic,’ or one who degrades the scriptures.)

“You have superseded me and violated the Vedic injunctions. Thus, because you have broken the law, the son that will be born to you will be known as Jaraśastra and he will increase your dynasty. Because of his origin from fire, his descendants will be known as Magas. Because of his origin from soma, they will be considered as brāhmaṇas. They will be known as Bhojakas due to his association with the sun. All this they will declare as divine.” (Bhaviṣya Purāṇa, Brahma Parva)

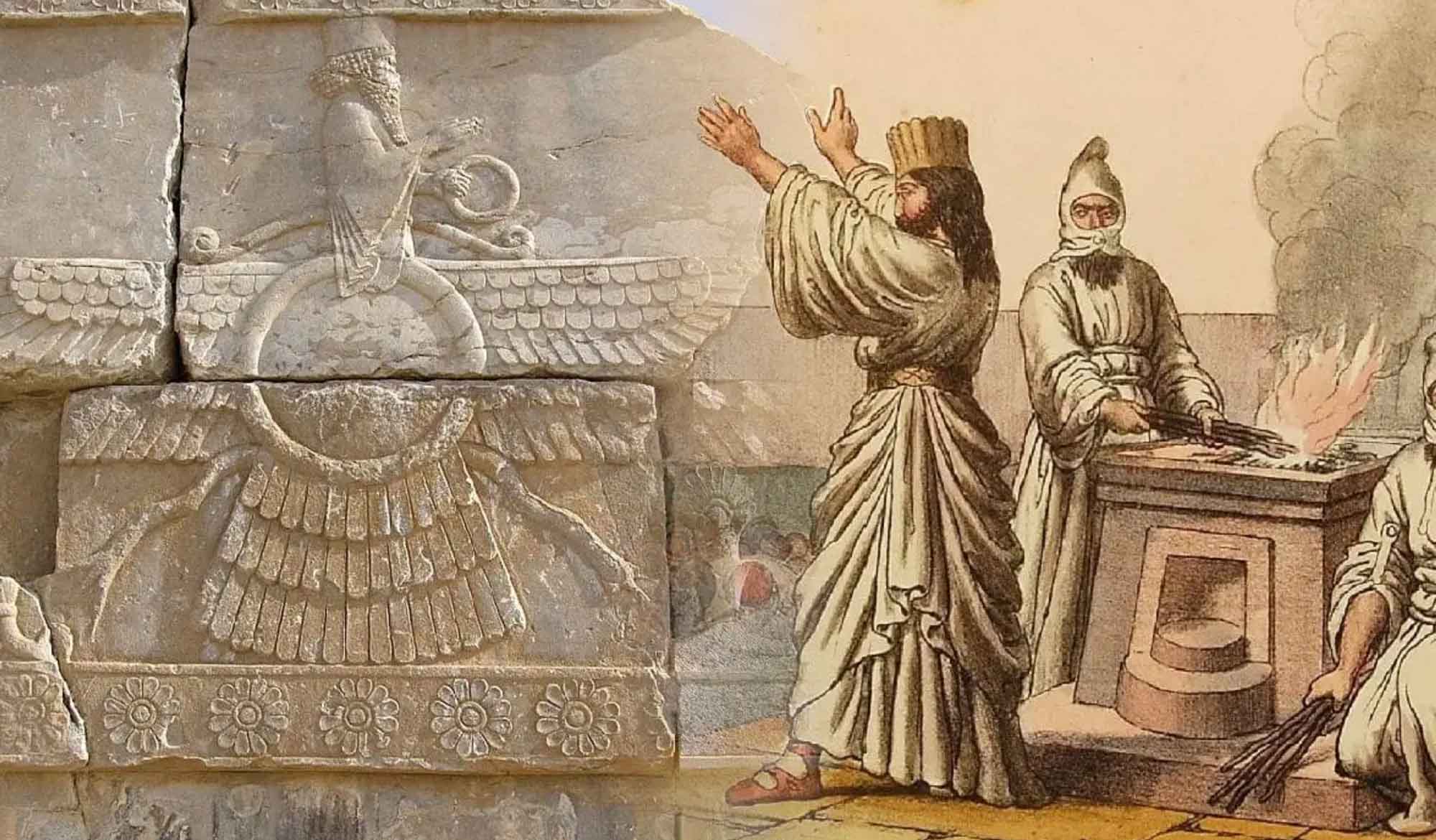

Over time Jaraśastra became known as Zarathustra (Persians pronounce ‘j’ as ‘z’), and the Greeks called him Zoroaster. The religion we know today as Zoroastrianism is the religion of Zarathustra. Zarathustra’s religion began to gain popularity in Persia after the Persian monarch King Vishtaspa became its first patron. Over time, Zoroastrianism became the state religion of Persia, and was extremely influential under the emperors Cyrus, Xerxes, and Darius.

So what was so different about Zarathustra’s new religion as opposed to the Vedic tradition? For one thing, Zarathustra reversed the roles of the Devas and the Asuras.

dvau bhūta-sargau loke daiva āsura eva ca

viṣṇu-bhakto smṛto daiva āsuras tad viparyayaḥ

“There are two classes of beings in the created world. One consists of the materialistic and the other the spiritually inclined. The devotees of Lord Viṣṇu are the Devas, whereas those just the opposite are called Asuras.” (Padma Purāṇa)

Zarathustra took the Asuras to be divine beings, and the Devas to be demons. He made Ahura Mazda (Asura Majda) the supreme god of his religion, and created an equally powerful adversary named Angra Mainyu. In the Zarathustra’s writings known as the Avesta, Ahura Mazda is the manifestation of order in the cosmos, and Angra Mainyu and his minions (the Devas) are the forces of chaos and destruction.

“The first of the good lands and countries which I, Ahura Mazda, created, was the Airyana Vaeja, by the Vanguhi Daitya. Thereupon came Angra Mainyu, who is all death, and he counter-created the serpent in the river and Winter, a work of the Devas. The second of the good lands and countries which I, Ahura Mazda, created, was the plain which the Sughdhas inhabit. Thereupon came Angra Mainyu, who is all death, and he counter-created the locust, which brings death unto cattle and plants. The third of the good lands and countries which I, Ahura Mazda, created, was the strong, holy Mouru. Thereupon came Angra Mainyu, who is all death, and he counter-created plunder and sin.”(Vendidad, Fargard 1.1-3)

Thus, the theological concept of God vs. Satan originally stems from Zarathustra. Prior to the appearance of Zarathustra we do not find this type of theory. From the Vedic perspective, all apparent contradictions are accommodated in the Absolute Truth. Order and chaos are seen as different transformations of the Lord’s energy, not two superior beings in conflict with one another.

Zarathustra’s philosophy also does not consider concepts such as karma, liberation, or divine service. Zarathustra believed that all souls are born pure, but Angra Mainyu corrupted the world and the people within it. There is no idea of saṁsāra, or the repeated cycle of birth in death in Zoroastrianism. According to Zarathustra, living beings have but one life to attain perfection, and one can create ‘paradisa’ or heaven on earth by performing humanitarian works, and focusing on social justice.

Many of the stories contained in the Avesta are originally from the Vedas but have been altered in order to accommodate Zarathustra’s belief system. New religions were not so easily accepted in ancient times, so they often retained some connection with old traditions by employing stories and characters from those older narratives. A classic example of this is the Avestan legend of Yima, which takes three distinct Vedic stories and amalgamates them into one.

Prior to Zarathustra’s arrival in Persia, the people worshipped many different gods, spirits and ghosts. Since Persia was previously part of ancient Bharata, the people also worshipped Vedic gods such as Mitra (Mithra), Varuṇa, and Vāyu. Zarathustra kept these names in his religion, but gave them new identities. Zoroastrian priests even wear a sacred thread over their left shoulder (known as a koshti) like that of a Vedic brāhmaṇa.

Zoroastrians worship fire, and regard fire sacrifices or yasna (Skt.yajña) to be a manifestation of cosmic order. Zoroastrians believe fire to be divine, thus they never cremate their dead since that would contaminate the purity of fire. Instead, they prefer ‘sky burials’ where animals and birds gradually dispose of human remains.

Zarathustra’s death is said to have happened while he was praying in a fire temple. According to Persian scholars, the temple was burned down by enemies of the religion, and his body was never recovered. We find a similar account of Zarathustra’s fate in the Ṛg Veda:

“Burn up all malice with those flames, O Agni, wherewith of old thou burnest up Jarutha,” (Ṛg Veda 7.1.7)

“O Agni (fire god), Vasiṣṭha kindles you – destroy the malignant Jarutha. Worship the object of many sacrifices. The Devas, on behalf of the wealthy priest of this sacrificial ceremony, offer their praise to you, O Jātavedas (Agni).” (Ṛg Veda 7.9.6)

Over a period of several hundred years, Zarathustra’s religious ideas entered Greece, Rome, and Jerusalem, planting the seeds of monotheism and morality into western soil. Despite their limited understanding of theology and philosophy, the Persians were morally principled people, and quite sophisticated when it came to political diplomacy.

In 539 BCE, the Persian Emperor Cyrus conquered Babylon and freed the Jews who were imprisoned under King Nebuchadnezzar. Afterwards, Cyrus helped the Jews construct the temple of Solomon in Jerusalem and sent Zoroastrian priests such as Ezra to help with the organisation of their religion and people. Cyrus is mentioned in the Torah as a messianic figure. Prior to their freedom from Babylon, the Jews worshipped many gods such as Yahweh, Baal, Ishtar, and Moloch. Baal for instance, was the god of storms to whom farmers made offerings for good rainfall. Ishtar, (from whom we get the word ‘Easter’) was the goddess of fertility, and Moloch was the god of wealth. Yahweh, who later became the one true god of the Israelites, was the god of war and initially had a consort named Asherah.

The transition of the Israelites from polytheism to a monotheistic religion is recorded extensively in the Torah, and culminates in the ten commandments given by Moses. Perhaps it is also no coincidence that God spoke to Moses through the medium of a great pillar of fire on top of a mountain, something which would bare a striking resemblance to the Zoroastrian fire ritual at that time.

“Thou shalt have no other gods before me. Thous shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the LORD they God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me.” (The Bible, Exodus 20)

Greek philosophers such as Heraclitus and Pythagoras were also fond of Zarathustra’s ideas. Heraclitus was the court philosopher for Emperor Darius, and derived his principle of ‘logos’ from Zarathustra’s writings. Plato accredited these two philosophers as his greatest influences.

Persian religious thought entered Rome through the cult of Mithras (originally the Vedic sun-god, Mitra), an esoteric branch of Zoroastrianism which centred on Mithras as a messianic saviour figure, who was the mediator between the forces of good and evil. Mithraism quickly rose as the most popular religion of the Roman empire, due to its appeal to soldiers.

Mithras (the sun) was said to die every year on the winter solstice, and was born again on the 25th of December. Mithras also had twelve disciples corresponding to the twelve months of the year (it is also interesting to note that in the Vedic scriptures, there is mention of the twelve Ādityas – solar deities who represent the twelve months of the year. Mitra is one of these deities).

Priests of the Mithras cult were called Magi (similar to the aforementioned Magi, the descendants of Jaraśastra) and wore colourful hats and silks during rituals. The most popular Mithriac ritual consisted of the sacrifice of a bull symbolizing the creation of the universe. Over time, the killing of the bull was discontinued, and wine and bread were given to initiates to symbolise the blood and body of the ritual offering.

Eventually Roman leaders became disturbed that the religion of their enemy (Persia) had become so popular in the Empire, thus they made a plan to establish a new state religion. They preserved many of the cult’s rituals and practices, but concealed them in their newly branded state religion – Christianity.

In Roman Catholicism today we still see many of the same rituals, attire, and doctrines originally found in the Mithras cult. The concepts of a saviour figure, God vs. the Devil, and even the Eucharist have their roots in Persian Zoroastrianism. There is, of course, also an undeniable influence from Judaism, Mesopotamia, and Egyptian religions on Christianity.

Monotheism reached the west through Zarathustra, and although obscured by compromise and political agendas, it brought a spark of truth along with it in the form of monotheism. However, a spark is not enough to drive out the darkness of ignorance. It is no coincidence then that due to such ignorance, some of the bloodiest conflicts in human history have been fought based upon the ideologies found in the Abrahamic religions.

When people fail to grasp the truth, they concoct religions. All these various religions battle for supremacy, but all eventually fall short in presenting an accurate conception of reality. To fully understand the Supreme Reality and our connection with that, one must discover the source of perfect knowledge – not a dim reflection perceived through man’s imperfect senses.

Related Articles

- 📖 When Wise Men Speak Wise Men Listen by Swami B.G. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja (Book)

- Greater Than the Upaniṣads and the Vedas by Śrīla Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Deva Gosvāmī

- Religiosity – Real and Apparent by Śrīla A.C. Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda

- Kṛṣṇa – The Supreme Vedāntist by Śrīla A.C. Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda

- Rational Vedānta by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Real Religion is not Man-made by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- More on ‘Real Religion is Not Man Made’ by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- More on Christianity: Only Kṛṣṇa Consciousness Can Enhance Kṛṣṇa Consciousness by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Jesus as a Perfect Christian by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Swastika and Cross by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Star of David or Star of Goloka? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Does God Exist? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Tad Viṣṇoḥ Paramaṁ Padaṁ by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Have the Vedas Advanced Civilization? by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- The Position of The Bhāgavata Amongst Religious Scriptures by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- Avatāras in Every Species by Śrīla Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja

- The History of the Bhagavad-gītā by Swami B.V. Giri

- Jesus in the Vedas by Swami B.V. Giri

- The Great Flood – Are Manu and Noah the Same Person? by Kalki Dāsa

- Zarathustra and The De-evolution of Theism by Kalki Dāsa

Further Reading

- Buddha-Gayā by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- ‘Hindu’ by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- Darśana-Śāstra (Philosophical Treatise) by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- Sukhera Viṣaya (A Matter of Happiness) by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- Śrī-Mūrti-sevā o Pautalikatā (Deity Worship and Idolatry) by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- The Hindu Idols by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- On Durga Siva and Kali in Their Exoteric Aspects: A Criticism on Max Muller by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- Vedānta Darśana (The Vedānta Philosophy) by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

- The Bhagavat – It’s Philosophy It’s Ethics and It’s Theology by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

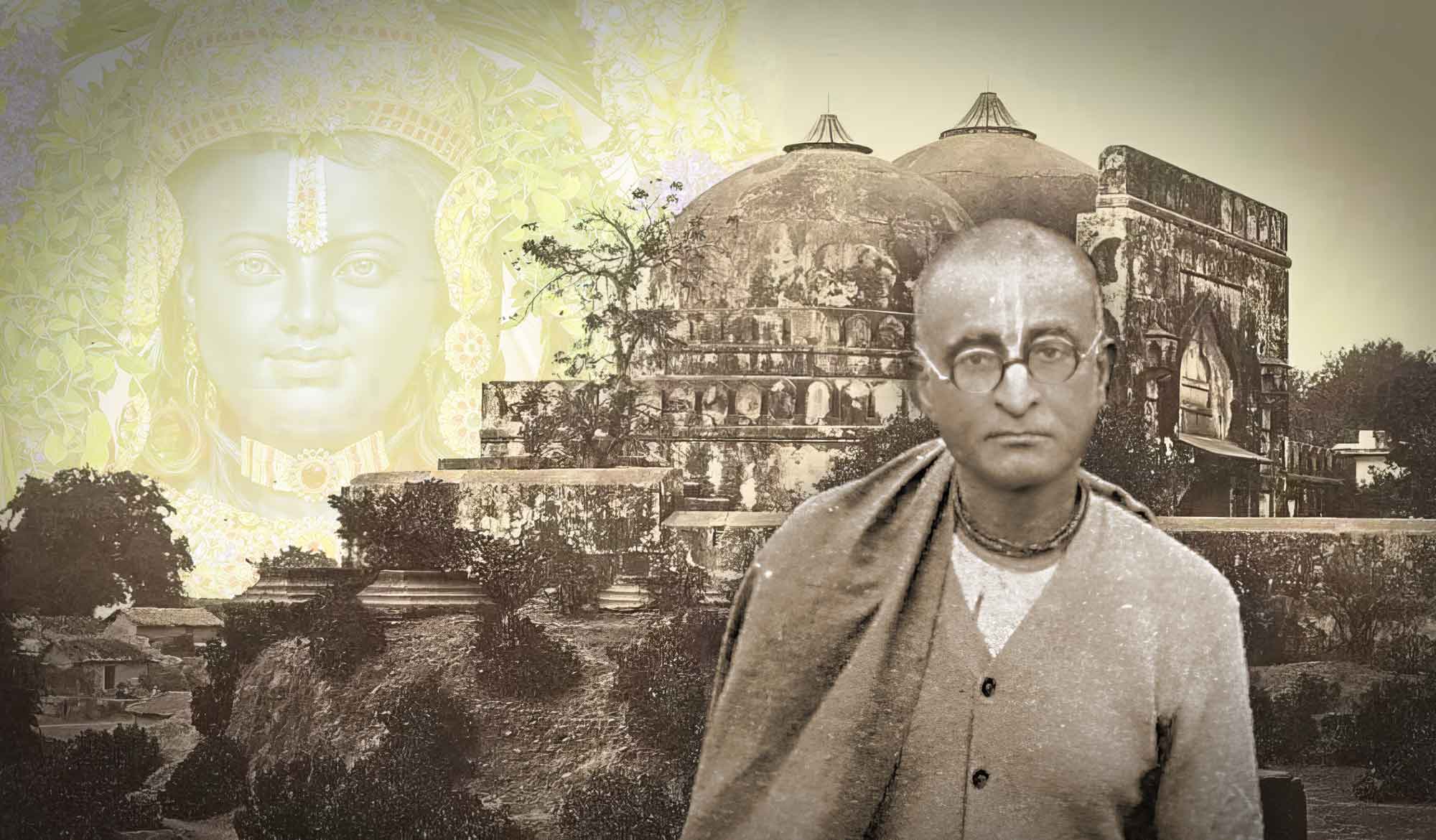

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.

Pilgrimage with Swami Narasiṅgha – Part 7: Keśī Ghāṭa

Continuing with our pilgrimage series, this week Śrīla Narasiṅgha Mahārāja takes us to Keśī Ghāṭā where he tells us about Madhumaṅgala’s meeting with the Keśī demon, what Keśī represents, and how Śrīla Prabhupāda almost acquired Keśī Ghāṭa. Mahārāja also narrates his own experience. This article has been adapted from a number of talks and articles by Narasiṅgha Mahārāja.

Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram with the Narasiṅgha Sevaka Commentary – Verses 61-65

In verses 61 to 65 of 'Prema Dhāma Deva Stotram', Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja narrates the pastime of Śrī Caitanya at Caṭaka Parvata In Purī and explains how the scriptures produced by Brahmā and Śiva are ultimately searching for the personality of Mahāprabhu who is merciful too all jīvas, no matter what their social position.

Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā

With the forthcoming observance of Śrī Rāma Navamī, we present 'Prabhupāda Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s Visit to Ayodhyā' written by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda from The Gaudīyā magazine, Vol 3. Issue 21/ In December 1924, after visiting Benares and Prāyāga, Sarasvatī Ṭhākura visited the birth-site of Śrī Rāmācandra in Ayodhyā.

Śaraṇāgati – The Only Path to Auspiciousness

In this article, 'Śaraṇāgati - The Only Path to Auspiciousness', Dhīra Lalitā Dāsī analyses the process of śaraṇāgati (surrender) beginning with śraddhā (faith). She also discusses the role of śāstra and the Vaiṣṇava in connection with surrender.